Arquivo para a ‘Linguagens’ Categoria

Totalitarianism and innocent lives

In war the first victim is the truth, a phrase attributed to Aeschylus of ancient Greece, but the tragic thing is the proportion of innocent victims, pure and elevated souls that war consumes because of the dread that totalitarian leaders have of freedom, free people and true humanism.

attributed to Aeschylus of ancient Greece, but the tragic thing is the proportion of innocent victims, pure and elevated souls that war consumes because of the dread that totalitarian leaders have of freedom, free people and true humanism.

There are countless cases, from hospitals and schools being bombed to cases of torture and cruelty to people who would bear great fruit for an elevated humanity, and that’s exactly why sick minds fight them.

I discovered among these various names, through a student, a Jewish woman named Etty (Esther) Hillesum, a Dutch daughter of Dutch father Louis Hillesum and Russian mother Rebecca Bernstein (Riva), a professor of ancient languages, from whom the interest in languages was probably born, but she goes to study Slavic languages, perhaps inspired by her mother, and then takes a master’s degree in law.

Her diaries and letters were written during the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam, and among the first books I came across were “Une vie bouleversée” (A Life Turned Upside Down) and 15 Days of Prayer with Etty Hillesum (published in Portuguese by Paulinas).

One of her phrases “inside me there is a deep well”, where inside there is sand and stones that prevent you from reaching something clearer, reveals a mystical path and the search within her to reach a deeper interiority, it is a refuge, I would say a spiritual resistance to Nazism and the climate that was generated around her.

Her relationship with psychiatrist Julius Spier (who was influenced by Karl Yung), initially for treatment and then for personal involvement, awakened her intellectuality, and in March 1941 she began to write her first of eight diaries.

In June and July 1942, he deepened his mystical dialog, writing: “God has become an interlocutor…” and it is in this context that we can talk about his writings on prayer.

He wrote in “15 Days of Prayer with Etty Hillesum”: “He took me by the hand, so to speak, and said to me: ‘That’s how you have to live’.” On the first day, he said of the second: “An hour of peace, you have to learn … I’m going to turn inward … half an hour of gymnastics and half a prayer of meditation”, the third day: ‘Hineinhorchen: listening inwardly’, listening to oneself, to others and to God.

This is how Etty’s itinerary goes: day four: “forgive my parents and their limits”, day five: “surrender to yourself and to your own guardianship”, in short, of a pure and innocent soul who indicates not just a path of repetitive and meaningless prayers, but an interior path.

One of the millions of innocent souls who died in concentration camps, she met her death in the Auschwitz camp at the young age of 29. Her writings are pure and profound, reminiscent of the purity of children and of people who live a human humanity.

Ferrière, P., Meeûs-Michiels, I. (2016) 15 dias de oração com Etty Hillesum (15 days of prays with the Etty Hillesum). Brazil, São Paulo: Paulinas editions.

Totalitarianism and political ontology

Wars always revolve around totalitarian governments, because they have a unilateral worldview, which despises the cultures and views of other peoples and thus wants to subject their peoples, who generally accept different cultures, to a single worldview.

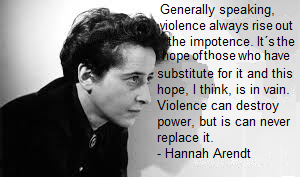

Hannah Arendt faced up to these regimes in her 1951 book, “The Origins of Totalitarianism”. She was convinced that after the end of the Second World War, the problem didn’t end there; she spoke of hell, nightmares, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, onions and even the ugliness of an omelette, among many other things, when the stories of Auschwitz came into her hands.

In trying to describe the totalitarian experience, Arendt was faced with the dilemma of how this experience could not be explained, not by political philosophy or traditional concepts, not just by the culmination of a process of developing something from a past, but in what Heidegger called the “forgetting of being”.

I’m reminded of a striking phrase by Lygia Fagundes Telles, who died on April 16, 2022, on her 99th birthday: “There is no coherence to mystery or logic to absurdity.” Dictators and their narratives only have logic in systematic propaganda, and in a claque of other fanatics who support them and identify with them, in short, a partial narrative of reality.

This form of narrative that Arendt wrote was opposed by a contemporary like Voegelin, about whom she responded to her analysis: “I have not written a history of totalitarianism, but an analysis in historical terms of the elements that crystallized in totalitarianism” (ARENDT, 2007, p. 403).

He also wrote in “The Crisis of the Republic” that the first fundamental difference between totalitarianism and the other categories present in history lies in the fact that totalitarian terror “turns not only against its enemies, but also against its friends and defenders”; a second difference would be its radicalism, which makes it capable of eliminating not only the freedom of action of individuals, as tyrannies did through political isolation, eliminating not only opponents but also unreliable allies, there is a clear parallel in today’s war.

In her note number 81, Arendt wrote: “The total number of Russians killed during the four years of war is estimated at between 12 and 21 million. In a single year, Stalin exterminated some 8 million people in Ukraine alone (see Communism in action, U. S. Government, Washington, 1946, House Document no. 754, pp. 140-1).” Again, the similarity with the current war is no coincidence, and after Butcha then Mariupol had a similar drama to Gaza (photo), but there are only ideological partial narratives.

The last topic of Arendt’s book is: “Ideology and terror: a new form of government”. If you’re interested in avoiding totalitarianism, just read it. It’s likely that we’ll become aware of this terror and stop feeding it in our day-to-day lives.

Arendt, H. (2007) Origens do Totalitarismo. Trad. Roberto Raposo. Brazil, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras..

Believe in divine protection and do good

Despite the climate of war, we must wish for peace. We warned in yesterday’s post that an escalation was imminent and it has happened, the climate and hate speech on both sides in the current global polarization is advancing and only those who continue to do good will be at peace.

We warned in yesterday’s post that an escalation was imminent and it has happened, the climate and hate speech on both sides in the current global polarization is advancing and only those who continue to do good will be at peace.

It seems heroic, innocent or even childish to continue to wish for and do good, but this is the only way not to fall into the trivialization of evil, polarization and inhuman discourse.

Yesterday, on Monday night in Brazil and early Tuesday morning in Israel, more than 180 missiles from Iran were launched at Israel, hypersonic missiles that traveled in 12 minutes until they hit Jewish soil; the number of victims and targets hit were not disclosed.

The involvement of the Arab world, Turkey, Lebanon and Syria have already declared their support for the attack, which had Palestinian celebrations in Gaza, takes the confrontation to a global scale, in the United States, Biden asked the forces in the area to defend Israel, which promises retaliation to Iran.

The possibility of the closure of the Gulf of Oman will affect the price of oil worldwide and, with it, the cost of products that depend on transportation and global logistics.

Only by adhering to goodness, peace and your daily life can we remain emotionally balanced and serene, even in the face of adverse circumstances, where everyone gives in to panic, hatred and the trivialization of evil.

For the philosopher Hannah Arendt, the banality of evil is the phenomenon of our character’s refusal to reflect and the tendency not to assume the consequences of actions that do not assume the consequences of evil, and thus prevent us from adhering to the good.

We only have protection in our spirit and soul when we resist the temptation to evil, what the philosopher and educator Edgar Morin also calls “resistance of the spirit” in the midst of polarization, hatred and war; by doing good actions we attract peace around us and divine protection.

The good and political ontology

Although the philosophical discourse on the good is broad and varied, modernity has lost part of this foundation when it is linked to the question of Being. In the political dialogue, for example, the development of Hannah Arendt and her works: “The Banality of Evil” and “The Human Condition”, or Freud’s “The Evil of Civilization” or Paul Ricoeur’s “The Symbolic of Evil” do not appear.

good is broad and varied, modernity has lost part of this foundation when it is linked to the question of Being. In the political dialogue, for example, the development of Hannah Arendt and her works: “The Banality of Evil” and “The Human Condition”, or Freud’s “The Evil of Civilization” or Paul Ricoeur’s “The Symbolic of Evil” do not appear.

The latter three can rework, in tragic dimensions, what we claim is the absence of a political ontology, what Hannah Arendt seeks in her texts.

Paul Ricoeur, explaining the symbolism of evil, wrote of individual attitudes that seek to “console” the victims of evil as a causal motive:

“To people who suffer and who are so ready to accuse themselves of some unknown fault, the true pastor of souls will say: God certainly didn’t want this; I don’t know why; I don’t know why…” (Paul RICOEUR, ‘Le scandale du mal’, op. cit., p. 60), looking at the origin of an evil, which the majority cannot explain, although they feel it.

The traditional philosophical discourse on the good revolves around either utilitarianism (the good is what maximizes happiness, in Stuart Mill), deontologism (the good is acting in accordance with moral duty) and eudaimonism (the supreme good is happiness, achieved through virtue).

Kant elaborates that the supreme good is the good will, that is, acting out of duty and not inclination, and so in contemporary philosophy (with an idealist foundation) the good ranges from virtue ethics to care ethics, but the absence of foundational values on evil ends up incorporating relativism and falls into the political discourse of populism and modern sophism.

Although the Greeks touched on the ontological question, the idea of Platonism that the good is the highest form of reality, the cause of what exists and the ultimate goal of knowledge, modernity is paralyzed under the aegis of an evil that is not only structural, but that affects being: Arendt’s banality of evil and Freud’s civilizational malaise.

Arendt shows that there is a fundamentally political gap in current thinking, which falls into the category of the plurality of philosophical thought. Before Hitler’s rise, Arendt’s search went on to other philosophical questions that also went in the direction of the good. In her doctoral thesis, supervised by Karl Jaspers, she discussed “The concept of love in St. Augustine”, but then she revisited the ontological question and went on to analyze the question of totalitarianism.

On the question of Love (agape) in his doctorate, it remains unfinished, according to his own supervisor, but even if evil seems to prevail, it is the good that we must pursue and only it can free us from the historical condition where evil seems to triumph.

Truth, language and method

The understanding of any phenomenon necessarily involves language and method, language as a means of communicating the phenomenon and method as a strategic path by which the truth can be reached on some issue.

necessarily involves language and method, language as a means of communicating the phenomenon and method as a strategic path by which the truth can be reached on some issue.

Dogmatic and ideological truths have led to narratives and distortions of reality, even those that pass through the imaginary, which is not necessarily an untruth, but often an analogy or metaphor to tell the truth.

Language as the “dwelling place of being” is for the phenomenological and ontological interpretation of truth, i.e. that which goes through the question of the “being” of the “being” is the basis for communicating the truth between source and destination, but it cannot be confused with sender and receiver.

When we have an “entity” as a means of communication, be it analog or digital (another confusion is to give analog an ontological category), it means that it is restricted to being just a “means” of communication, so it makes the message encoded in a signal, for example an analog acoustic wave (fm radio for example) or a signal encoded in zeros and ones, in this case digital, both of which cannot be interpreted as “the dwelling place of being”, but only code, that is, something more conducive to the entity than to being.

The signal aimed at reducing noise and authenticating the message that has been coded should not be confused with the message itself, since it comes from Being and carries within itself not a logic, but an onto-logy, in other words, something originally from Being.

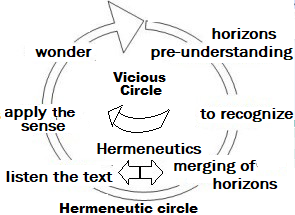

It is in this ontology that we can understand the meaning of dialogue, even between logically opposed messages, since ontologically they can share a fusion of horizons and can then create a method, developed by Heidegger and formalized by Hans-Georg Gadamer.

Gadamer’s explanation of the hermeneutic circle is expressed as:

“The circle must not be degraded to a vicious circle, even if this is tolerated. In it there is a positive possibility of the most original knowledge, which, of course, will only be adequately understood when interpretation understands that its first, constant and ultimate task remains not to receive beforehand, by means of a ‘happy idea’ or by means of popular concepts, either the previous position or the previous vision, but to ensure the scientific theme in the elaboration of these concepts from the thing itself”. (GADAMER, 1998, p. 401).

This is why Gadamer’s studies, entitled Philosophical Hermeneutics, cover many peculiar aspects of his studies and writings, with a contribution that goes beyond philosophy itself, linguistics and, to a certain extent, theological hermeneutics, from which came the work and studies of Schleiermacher, who spoke of “spheres” and “circles” in his studies on hermeneutics.

It is only in this idea of the fusion of horizons, of going beyond the vicious circle, that we can understand an inverse reasoning of one against all, and understand the dialog between opposites.

GADAMER, Hans-Georg (1998). Verdade e Método: Traços fundamentais de uma hermenêutica filosófica. Transl. Flávio Paulo Meurer. 2a. ed. Brazil, Petrópolis: Vozes.

Narrative and truth

It’s not just some thinkers like Edgar Morin, Peter Sloterdijk and Mario Bunge who complain about the difficulty of elaborating thought in a truthful way, the fundamentals have been lost and narratives dominate even areas like science and religion, not to mention politics which is the realm of narratives, peace, climate and social security are part of rhetoric.

Peter Sloterdijk and Mario Bunge who complain about the difficulty of elaborating thought in a truthful way, the fundamentals have been lost and narratives dominate even areas like science and religion, not to mention politics which is the realm of narratives, peace, climate and social security are part of rhetoric.

In Byung-Chul Han’s book “The Crisis of Narration” he recovers an essay by Hungarian writer Peter Nadás “Betsutsame Ortsbestimmung” (I don’t think there is a Portuguese translation, but Han translated the title as Location pending), which tells the story of a village where in the center stands a huge wild pear tree.

Nadás describes this village as a narrative community that gathers around the pear tree “on warm summer evenings” for “ritual contemplation” and ratifies the “collective content of consciousness” (Han, 2023, p. 121), where there is “no opinion about this or that, but uninterrupted narration of a single great story” (Há, p. 122) and where they used to “sing softly … Today there are no more of these trees and the singing of the village has died down” (Nadás, apud Han, 2023, p. 122).

The Korean philosopher adds: “That ‘ritual contemplation’ that ratifies the collective content of consciousness gives way to the noise of communication and information” (Han, p. 122), “that ‘singing’ that tunes the villagers into a story and thus unites them” (Idem).

What they experience from “noisy” communication “does not create any social cohesion, it does not create a We. On the contrary, it dismantles both solidarity and empathy” (Han, 2023, p. 123).

Han’s philosophical critique is clear: “But not all the constitutive narratives of a community are based on the exclusion of the Other, insofar as there is also an inclusive narrative that does not cling to an identity” (Han, 2023, p. 124) and even quotes Kant’s Perpetual Peace, despite all its conservative idealism.

His universalism is clear: “Every human being enjoys unrestricted hospitality. Every human being is a citizen of the world … He [Novalis] imagines a ‘world family’ beyond nation and identity. He elevates poetry as a form of reconciliation and love” (p. 125).

The author, based on Novalis, also refers to the issue of complexity that contemplates the whole: “The individual lives in the whole and the whole in the individual. It is through poetry that the highest sympathy and coactivity originate, the most intimate communication” (Han, 2023, p. 125).

Han, B.-C. (2023). A crise da narração. Transl. Daniel Guilhermino. Brazil. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes.

Sophists and relativism

The political issue and the current polarization involve an age-old problem: sophistry. Its origin in ancient Greece is when Plato started a school for training philosophers to create men of the “polis” who would serve not only authoritarian governments, but the Greek city-states.

involve an age-old problem: sophistry. Its origin in ancient Greece is when Plato started a school for training philosophers to create men of the “polis” who would serve not only authoritarian governments, but the Greek city-states.

The speech in Theaetetus on the nature of knowledge, written in 369 BC, is where the confrontation between truth and relativism appears, at least clearly for the first time in philosophy.

In it, a character called “the Stranger from Elea”, who would have been a companion of both Parmenides and Zeno”, elaborates on three important figures in the Platonic school: the sophist, the politician and the philosopher, but in it he only did not write about the definition of the philosopher that would be investigated in other texts, but the politician for him, par excellence, would be the philosopher, who among other things should have ‘Aretê’, that is, virtues.

The reason there is a coincidence with current political discourse, and this origin of relativism, can be seen in the explanation he gives about reality and the image they seek to represent, both of which are not what they represent, but are clearly something else, for example the image of a house can look like and show very well what a house is, without being one.

Just as the image of a dog is characterized by not really being a dog, the content of a false speech is characterized by not being what it really is, both say something about the truth, but are in essence different things.

Despite this, an ontological contradiction remains in the discourse, as the Stranger emblematically announces: “such a statement presupposes being and not being”, Parmenides’ classic thesis, although the root of his thought is logical and not ontological.

Thus, appearance and image do not coincide with the real truth, although they may confuse an inattentive viewer, they are not the same thing, discerning them is an essential condition for exercising truth, so we may not remain in the truth when we embark on “images”.

There is a popular saying, it is not known who first said it, but in war the first thing that dies is the truth, and its more than tragic consequences lead to a crisis of who we really are as humanity and with our inalienable rights that are stolen.

Towards a political ontology

Various authors talk about what power is, from the classic contractualists (Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau), through the modern readings of Marx, Weber, Tocqueville, Bobbio and Norbert Elias, to Byung-Chul Han (psychopolitics) and Foucault (biopolitics), but Hannah Arendt went further by envisioning political ontology and completely escapes Hegelian thinking.

from the classic contractualists (Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau), through the modern readings of Marx, Weber, Tocqueville, Bobbio and Norbert Elias, to Byung-Chul Han (psychopolitics) and Foucault (biopolitics), but Hannah Arendt went further by envisioning political ontology and completely escapes Hegelian thinking.

In her book from the late 1960s (and therefore Arendt’s Arendt’s maturity), she criticizes the “new left” which thought of Fighting a world threatened by nuclear destruction and dominated by large state, administrations and they would be responsible for violence and ultimately the essence of all power, she writes.

If we turn to discussions of the phenomenon of power, we quickly realize that there is a consensus among political theorists, from left to right, that violence is simply the most flagrant manifestation of power. ‘All politics is a struggle for power; the basic form of power is violence,’ said C. Wright Mills, echoing Max Weber’s definition of the state as ‘domination of man by man based on the means of legitimate violence, that is to say, supposedly legitimate violence. Wright Mills, echoing, as it were, Max Weber’s definition of the state as the ‘domination of man by man based on the means of legitimate, that is, supposedly legitimate, violence’”. (Arendt, 2001, p. 31)

For the author, following the Greco-Roman tradition, this concept bases power on consent and not violence, thus on a relationship of command and obedience.

The author notes that this concept is “a sad reflection of the current state of political science” (p. 36) and a natural identification of the traditional view of power and violence, since “power, vigor, force, authority and violence would be simple words to indicate the means by which man dominates man; they are taken synonymously because they have the same function” (idem) and this “virility” is often observed from Greece to the present day.

For the author, “power corresponds to the human ability not only to act, but to act in concert. Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only to the extent that the group remains united. When we say that someone is ‘in power’, we are really referring to the fact that they have been empowered by a certain number of people to act on their behalf” (p.36).

For the author it is necessary to review these concepts: power, vigor, force, authority and violence, since “violence would not identify any coercive act, but only that which operates, in the case of social relations, on the physical body of the opponent, killing him, violating him, in short, it seems to describe only the effective use of implements” (p. 37) and thus war.

Arendt speaks of “isonomy” where Chul Han speaks of “symmetry”, similar concepts, and so power is indeed that which “emerges wherever people unite and act in concert, but its legitimacy derives more from the initial being together than from any action that might then follow” (p. 41, with emphasis in my text).

What is needed is an action of “unity”, of “service” and, at best, as the one who serves the community and not the one who serves himself, and for this he will always need violence.

This requires an action of “unity”, of “service” and, at best, as a the best case scenario, as the one who serves the community and not the one who serves and for this you will always need violence.

ARENDT, H. (2001). Poder e violência. Brazil: Rio de Janeiro, ed. Relume Dumará.

The difference of the divine Love

Hannah Arendt’s reading of Saint Augustine in her doctoral thesis remains between these two interpretations of human and divine love.

in her doctoral thesis remains between these two interpretations of human and divine love.

To analyze this, Arendt interprets Augustine’s work as governed by three principles that appear without apparent contradiction. She increased Augustine’s dogmatic rigidity to the extent that Christianity was inserted into his thinking, this consisting of his passage from pre-theological, philosophical thinking to theological thinking, according to the author.

Thus the first part of the author’s thesis, entitled “Love as desire: the anticipated future”, approaches love from a philosophical perspective of continuity with Hellenic thought, in which love is seen as a disposition that is always driven by lack, by something that is not possessed, but which one hopes to have, as a means of achieving happiness, thus desire is something not yet achieved while Love is the desire obtained, and this is philosophical.

These two types of love are given two names by Augustine: caritas and cupiditas. They differ in their love for the object they love, “but both right and wrong love (caritas and cupiditas) have this in common – desirous longing, that is, appetitus”, writes the author.

Caritas is pure, true love, because it desires God, eternity and the absolute future, while cupiditas loves the world, the things of the world, here it is pre-theological, because charity is not just a passing love, or desire for a passing good, but for the eternal.

Whether we are religious or not, we are between desire and possession, after we have obtained the desired object in general, and enjoyed the pleasure of this possession, cupiditas passes and something eternal remains if there is caritas in it, that is an Eternal Love, which gives an eternal possession and then does not pass away.

So the man who has this quest must withdraw into himself, and within himself, isolating himself from the world, he penetrates the Augustinian “quaestio”, the guiding thread that Arendt pursues: “for the more he withdrew into himself and collected himself in the dispersion and distraction of the world, the more he became a ‘question for himself’,” wrote the author.

Every philosophy has a basic question, and Augustine’s becomes theological: “What do I love when I love my God?” (Confessions X, 7, 11 apud Arendt p. 25), even if it is “in the world”.

Thus the second part of her thesis is called “and ‘Creature and Creator: the remembered past’, in book X of Confessions. “Memory, then, opens the way to a transmundane past as the original source of the very notion of a happy life,” the author wrote about Augustine.

In proposing a relationship with the Creator, man does not lose himself, but finds himself, and this is different from any kind of worldly attachment, the god of money, consumption or desire.

Arendt, Hannah. (1996) Love and Saint Augustine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Hannah Arendt and Love´s Mundi

Hannah Arendt was, in our view, instigated by her existential drama, and within it, to take up the question of Love as an essential issue from an early age, writes Safransky:

by her existential drama, and within it, to take up the question of Love as an essential issue from an early age, writes Safransky:

“At the beginning of 1924, an 18-year-old Jewish student arrived in Marburg wanting to study with Bultmann and Heidegger. She was Hannah Arendt. She came from a good assimilated Jewish family in Könisberg, where she had grown up. By the age of 14, her curiosity had already been aroused. She read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and mastered Greek and Latin so well that at the age of 16 she founded a study and reading circle for ancient literature. Even before her final exams at the Könisberg high school, she spent a season in Berlin, where she read Heidegger and took lessons from Romano Guardini (a specialist in Kierkegaard),” Safranski wrote about Hannah.

While still a teenager, the thinker who had already formed a philosophy circle as an adolescent, wrote her first concerns, Hannah Arendt wrote the poem Consolation (Trost):

“The hours pass, Die Stunden verrinnen / The days pass, Die Tage vergehen, / There remains one grace Es bleibt ein Gewinnen / The simple persisting. Das blosse Bestehen.” (Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt, For Love of the World, p. 53).

In a letter from Heidegger to her, “And what can we do but open ourselves, but let it be what it is? To let ourselves be in such a way that love becomes for us a pure/chaste joy (reine Freude) and the source of each new day of life. To be elevated to what we are. In any case, it would be possible for one of us to ‘say’ and open up to the other. We can only say, however, that the world is no longer mine or yours, but ours”.

Thinking of the world as “ours” and not mine is a necessity of our time, an essential step towards our world problems. When we read Hannah’s doctoral thesis “The Concept of Love in St. Augustine” (ARENDT, 1998), we understand that there was an attempt to go beyond the existential and get to the essence of love, and the search for amor mundi.

When reading Augustine of Hippo, the subject of her doctoral thesis, she observes the separation between love and enjoyment: “this joy lies in loving love without inscribing it in something particular and fleeting”, and then emphasizes: “Love hopes to find its own fulfillment in eternity” (Arendt, The Concept of Love in Saint Augustine, p. 35).

Despite this reference to “eternity”, Arendt doesn’t get to that theological virtue: love, which must be combined in an “existential” way as faith and hope, since in eternity, for those who believe, faith and hope will already be in fullness in Love.

ARENDT, H. (1998) O conceito de amor em santo Agostinho. Transl. de Alberto Pereira Dinis. Portugal, Lisboa: Instituto Piaget.

SAFRANSKI, R. (2000) Heidegger, um mestre da Alemanha entre o bem e o mal (biografia). Transl. de Lya Luft. Apresentação de Ernildo Stein. Brazil, São Paulo: Geração Editorial.