Arquivo para a ‘Antropotécnica’ Categoria

What is the crisis of idealism?

The scenario of the world’s involvement in wars is a difficult one. We need to understand what lies behind it, as it is a daily confrontation between minds, souls and economic interests that fight each other on a daily basis.

is a difficult one. We need to understand what lies behind it, as it is a daily confrontation between minds, souls and economic interests that fight each other on a daily basis.

In essence, they are defending a “free society” or a “society liberated from capitalism” without analyzing the origins of these thoughts and models in depth.

They reflect the crisis of contemporary thought, which is not only philosophical, religious or political, but also a loss of the foundations of what is human, nature and science itself.

Sloterdijk’s vision, expressed in his spherology in volume I Bubbles, shows that both the onto and anthropological phenomena are more essential than the relationship between subject and object, because they precede the spatial experience of Being-in (even if it’s not exactly what Heideger called In-Sein), which is the main criticism of contemporary idealism.

In the field of religion (and this can be extended to thought), the essayist Byung-Chul Han reflects that the “pathos of action blocks access to religion. Action is not part of the religious experience. In On Religion, Scheleiermacher elevates intuition to the essence of religion and contrasts it with action.” (Han, 2023, p. 154) It is worth remembering that Scheleiermacher reintroduced hermeneutics as a method and influenced modern phenomenology.

Scheleiermacher said verbatim (quoted by Han in Vita Contemplativa) in On Religion: “Its essence is neither thinking nor acting, but intuition and feeling. It wants to intuit the universe, […] it wants to listen to it devoutly, it wants to apprehend it in its childlike passivity and be filled by its immediate influences” (apud Han, p. 154), and also affirms ‘all activity in an awe-inspiring intuition of the infinite’ and says Han: ”Whoever acts has a goal before his eyes and loses sight of the whole. And thinking directs its attention to only one object. Only intuition and feeling have access to the universe, namely the whole of being” (Han, 154, idem).

This disregard for the whole being, taking only its particular social aspects, such as economic, ethnic or even religious aspects, is what Heidegger called the forgetting of Being, even though the Greeks worked on ontological aspects.

However, there are two convictions and different visions of idealism, or state idealism in two proposals, capitalism and socialism, not forgetting that Marx is also a Hegelian, although his group has been named “new Hegelians”.

And the crisis of democracy is a crisis of the state, a model that has been corrupted by megalopaths and dictators who know little or nothing about the interests and lives of ordinary people.

The current war is the crisis of this model, both willing to prove their superiority by imposing war, as the uruguyan writer Eduardo Galeano said: “No war has the honesty to confess, I kill to steal” and even more obviously they kill innocent civilians.

The sky can speak

Sloterdijk assumes the time that through the ages men “made gods speak”, this is also what he says about the “speech” of Jesus, and he says with historical propriety: “Finally, those who were invoked too much also made themselves known through the personal incarnation: sometimes they took the liberty of resorting to apparent bodies that came and went as they pleased.” (pg. 22), it is true and this means: Do not use God’s name in vain.

ages men “made gods speak”, this is also what he says about the “speech” of Jesus, and he says with historical propriety: “Finally, those who were invoked too much also made themselves known through the personal incarnation: sometimes they took the liberty of resorting to apparent bodies that came and went as they pleased.” (pg. 22), it is true and this means: Do not use God’s name in vain.

But historical reasoning helps better with the other alternative use of “God”: “… or they were condensed, “in the fullness of time”, into a Son of Man, into a saving Messiah. After Cyrus II, the king of the Persians famous for his religious tolerance, allowed the Jews who had been taken captive to Babylon to return to Palestine in 539 BC, putting an end to an exile of almost sixty years… The spiritual elite of the Jews became much more receptive to messianic good news — Second Isaiah set the tone for this.” (p. 22).

He correctly says when he calls Cyrus “panegyric” (worship of an abstract god), he did not convert or even abandon his beliefs in other gods, as “an instrument of God” he freed a people, the author also recalls Marcião who worshiped “the unknown god” that will make Paul call the Greeks a religious people, but states that the known God is the one that the apostle of the Gentiles (Paul) proclaims in the figure of Jesus, the Redeemer.

The issue of redemption pointed out by Sloterdijk from a historical point of view, has its meaning as these are moments in which “heaven opened”, but he sees it as a spectacle where “The oldest stage of evidence from sensitive and supersensitive sources is shown in the form of commotion of the participants generated by a “spectacle”, a solemn rite, a fascinating hecatomb.” (pg. 24) and this has been repeated throughout the ages, with great speakers and great “media experts”, but this will be the true God, of Augustine as Sloterdijk himself cites him (De vera religione).

He is also right when he says about some who consider themselves to have “divine” gifts: “. In general, it was assumed that there were interpreters capable of associating a practical meaning with the encoded symbols” (pg. 25), but again not these false oracles that seek spotlight.

See how Jesus asks for the healing of a man born deaf/mute (Mc 7,34-36): “Looking at the sky, he sighed and said: “Ephphatah!”, which means: “Open up!” Immediately his ears opened, his tongue loosened, and he began to speak without difficulty. Jesus insistently recommended that they not tell anyone. But, the more he recommended, the more they disclosed”, this small detail that appears in many miracles, do not disclose, that is, it is not a spectacle, it does not mean not doing it well, however, with a sacred sense.

The meaning of this cure is deeper, in addition to making a world deaf from birth hear and speak, reading previous excerpts from the evangelist Mark we find the absurd idea (present in today’s “religious” circles), using the idea of a Syro-Phoenician woman whose daughter had a “demon”, it is not the idea that an illness or some bad occurrence is “punishment from heaven”, as it is from the heart of man that “impure” things come out: evil, greed, etc.

The Ephphatah (open sky) said to cure a deaf-mute from birth is because it is not a common disease, someone whose life and cognitive system were not taught to listen and speak, did so immediately, it´s complex.

In dark times, it is necessary for the deaf to hear and the mute to speak, as there are those who want to remain silent.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024). Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

The universe was created

Whether or not the hypothesis of the creation of the universe by the Big Bang is valid (there is the hypothesis of the multiverse) at some point it appeared, Heidegger’s category of dasein being there is very expensive, but this is essentially the human of Being.

of the universe by the Big Bang is valid (there is the hypothesis of the multiverse) at some point it appeared, Heidegger’s category of dasein being there is very expensive, but this is essentially the human of Being.

Sloterdijk goes into this merit by writing: “Three hundred years after the death of the man who was venerated by his followers as the arrived Messiah, the Council of Nicaea established the dogma that the Lord Jesus Christ would be God of God and light of light, true God of the true God, begotten and uncreated—whatever that means.” (pg. 31), if the name of God bothers (and makes sense), creation was not created.

Recent photos from the James Webb Telescope intrigue scientists because apparently there was no slow creation, entire complex galaxies seem to be at the beginning of the Big Bang, and the force that moves them seems to be something truly extraordinary, unthought of by science.

As we said in the previous post, in addition to Jesus, for Sloterdijk also Socrates and Seneca must be examined, and they are historically close, he wrote: “What in common language is called “becoming human” designates, discounting extrapolations, a state of things that the Roman philosopher Seneca (1-65 BC), partly a contemporary of Jesus (4 BC-30 BC), for some time mentor of the young Nero [see] and, later, forced by him to commit suicide, revealed in the following sentence: sine missione nascimur — meaning: we were born with the certain prospect of dying” (pgs. 31-32).

Thus, one could separate the mortal from the important, but Sloterdijk thinks differently and writes: “Everyday levity is a mask for the timeless ghost of indestructibility; the preacher in Palestine and the philosopher in Rome take off this mask to testify that there is something indestructible that is not of a frivolous and phantasmatic nature.” (pg. 33), hence his disbelief in something “indestructible”, and the difference from the messianic preacher of Palestine is “resurrected”.

For him, Jesus distinguished himself in speaking: “but perhaps also just a fazn de parler [way of speaking] for “I” —, he came into the world, as he himself was led to say, to sign his teaching with his life.” (pg. 33), but his life was different as someone who came from another reality and knew it.

Thus he is trapped in seeing human realities as “ex machina”: “The man who called himself “Son of Man” spoke essential elements of his message from the cross, in which he ended up as deus fixus ad machinam [god stuck to the machine]” (pg. 33), but it is not, he will examine the writings of Ignatius of Loyola (founder of the Jesuits) and Hegel, but he is stuck with Hegel’s notion of absolute, because he does not admit the universe complex that we now see through James Webb.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024). Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

The historical analysis of theopoetry

No one will be converted by reading Sloterdijk, he calls the term religion “nefarious”, but the term not the culture he seeks to delve into, about the term he states: “… especially since Tertullian reversed, in his Apologeticum (197), the expressions “superstition (superstitio)” and “religion (religio)” against Roman linguistic usage: he called the traditional religion of the Romans superstition, while Christianity should be called “the true religion of the true god”. In this way, he produced the model for the Augustinian treatise De vera religione [On true religion] (390), which marked an epoch, through which Christianity definitively appropriated the Roman concept” (pg. 20) and its reasoning and historical vision is much more accurate than the one that wants to appear as if Constantine created a “religion”.

he calls the term religion “nefarious”, but the term not the culture he seeks to delve into, about the term he states: “… especially since Tertullian reversed, in his Apologeticum (197), the expressions “superstition (superstitio)” and “religion (religio)” against Roman linguistic usage: he called the traditional religion of the Romans superstition, while Christianity should be called “the true religion of the true god”. In this way, he produced the model for the Augustinian treatise De vera religione [On true religion] (390), which marked an epoch, through which Christianity definitively appropriated the Roman concept” (pg. 20) and its reasoning and historical vision is much more accurate than the one that wants to appear as if Constantine created a “religion”.

Historical because the influence on Augustine of the Neoplatonists, especially Plotinus, is not only reasonable, but strong enough for what he will write, not in Vera religione, but in his Confessions, which is practically his testament and model of his conversion, Augustine leaves Manichaeism (two opposing poles in dispute) to discover the One (Plotinus’ category), the religion of Love, which earned Hannah Arendt a doctoral thesis.

However, the political action of religion is not denied, Sloterdijk writes, citing Virgil’s Aeneid: “No imperialism rises without the current positions of the constellations in the temporal sky being interpreted, both in the case of those in power and those aspiring to it. Added to them are advice from the underworld: “Tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento.” (pg. 26 quoting Virgil). In the figure above, Euripides’ representation of Medea from deus ex machina.

He is talking about cultural communities and quotes Constantine: “the symbolic or “religious” and emotional integration of larger units: of ethnicities, cities, empires and supra-ethnic cultural communities — the latter of which could also assume a metapolitical, or rather, anti-political character, as was clear in the case of Christian communities in the pre-Constantinian centuries” (pg. 25-26), when Christians were persecuted and this is history.

The church was already structured at this time: “The bishops (episcopoi: supervisors) were, in essence, something like praefecti (commanders, procurators) in religious attire; its dioceses (in Greek: dioikesis, administration) they resembled the previous imperial districts after the new subdivision made by Diocletius around the year 300; above all through them, the principle of hierarchy reached the ecclesiastical organization in formation…” (pg. 26), thus Constantine in 313 when he places the Catholic religion as the “official” religion [through the influence of his mother Helena] had little or almost no influence its structure.

In fact, in the Jewish heritage, it had already enshrined many rituals: “The mediological principle apò mechanès theós, in fact, deus ex machina, typical of scenic technique or religious dramaturgy, was in fact already in use in several Near Eastern rituals long before to emerge in the Athenian theater” (pg. 28), thus this “deus ex machina” was already present in Judaism.

The author recognizes the religious turn of Jesus: “The god-man, who called himself “Son of Man” inspired by Persian and Jewish sources — possibly a messianic title, but perhaps also just a fazn de parler [way of speaking] to “I” —, came into the world, as he himself was led to say, to sign his teaching with his life” (pg. 32), although he compares him with Socrates and Seneca who had “indispensable convictions”.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024) Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

Sloterdijk’s theopoetry

One of the greatest contemporary philosophers, of enormous influence on Byung-Chul Han, Sloterdijk is far from being a Christian or any type of religious person, but he is wise enough to know the enormous influence of religion on culture throughout the centuries and in our time.

of enormous influence on Byung-Chul Han, Sloterdijk is far from being a Christian or any type of religious person, but he is wise enough to know the enormous influence of religion on culture throughout the centuries and in our time.

What sky is he talking about then, he clarifies: “The sky we are talking about is not an object capable of visual perception. However, since time immemorial, when looking up, representations in the form of images accompanied by vocal phenomena were imposed: the tent, the cave, the vault; in the tent the voices of everyday life resound, the walls of the caves echo ancient songs of magic, in the dome chants in honor of the Lord in the heights reverberate” (p. 11), explains the author in your preliminary observation.

Mythological gods, the author based on the Greenfield papyrus (10th century BC), where we see: “Detail from the Greenfield papyrus (10th century BC)”: “The goddess of the sky, Nut, bows over the god of the earth, Geb (lying down), and of the god of the air, Shu (kneeling). Egyptian representation of heaven and earth” (p. 12, photo, Wikipedia Commons).

However, it is not a mythological essay either, he writes: “What we intend, in what follows, is to speak of communicative, luminous skies that invite raptures, because, corresponding to the task of poetological enlightenment, they constitute zones of common origin of gods, verses and pleasures” (p. 13).

It makes a curious metaphor with Mt 13:34, a passage so dear to Christians that says: “All this Jesus spoke in parables to the crowds. He spoke nothing to them without using parables, to fulfill what was said by the prophet: ‘I will open my mouth to speak in parables; I will proclaim things hidden since the creation of the world'” (Mt 13,34-35), it was necessary because it spoke of “communicative, luminous” heavens.

In his metaphor Sloterdijk says: “Deus ex machina, deus ex cathedra and without parables he told them nothing” (p. 13, about divine reality), and here the philosopher questions the contemporary world, which idolizes these contemporary gods ex machina and ex cathedra.

It will remind you of the theopoetry in the mouth of Homer, who had “speaking gods”, but it will also remind you of the passage in which Zeus rebukes “the willful manifestations of his daughter Athena”, and says to her: “My daughter, what word has escaped you from the barrier teeth?” (p. 15)

Of course, as Christians we do not talk about mythological gods, it reminds us of Christian semiotics where signs are important: “the zone of signs grows parallel to the art of interpretation. The fact that it is not accessible to everyone is explained by its semi-esoteric nature: Jesus already reproached his disciples for not understanding the “signs of the time” (semaîa tòn kairòn).” (pg. 25).

It is not about delusion or gross falsehoods about eschatological events, if they exist they are only bearers of these “signs” true oracles and prophets, or to use Sloterdijk’s term: theopoets who say things from heaven, such as poetry and clarity, even if use parables due to the difficulty of expressing them in everyday language and reality.

The signs of the times, dark as wars and alive as those who resist with the spirit of hope and peace, do not make tragedy like the Greeks a sign of revenge or intolerance, but of seeing beyond what the raw and naked reality seems to show.

Sloterdijk, P. Making the sky speak: on theopoetry, Trans. Nélio Schneider, Liberdade Station, 2024.

Inner life and happiness

We live in pure exteriority, modern man does not know the interior life, he is projected onto things and actions, he believes he can extract from it what is missing internally.

know the interior life, he is projected onto things and actions, he believes he can extract from it what is missing internally.

Byung-Chul Han in his essay “Vita Contemplativa” [contemplation life] quotes a short story by Walter Benjamin “Do not forget the best” in which he recalls a little shepherd boy, “who is allowed, on “a Sunday”, to enter the mountain of his treasures, but with the cryptic instruction: “don’t forget the best”. The best means not doing it.” (Han, 2023, pg 33).

Reading Being in modernity, Han writes: “The crisis of the present consists of everything that could give meaning and guidance to life and is breaking. Life does not rely on anything resistant to support it.” (pg. 87), recalls quoting Hanna Arendt who claims to “find uncertain shelter in the darkness of the human heart” which still has the ability to say: “to remember and say: forever” (idem) and remembers immortality in this aspect.

When contemplating the being that has a temporal dimension: “It grows long and slowly. The current short term dismantles it.” (pg. 89) and quotes Niklas Luhmann about the (current) information: “His cosmology is a cosmology not of being, but of contingency” (pg. 89 quoting Luhmann).

But it remembers immortality translated in this crisis as: “The search for immortality, for immortal glory, is, according to Arendt, “the source and center of the vita activa.” Human beings achieve their immortality on the political stage” (pg. 145), but true immortality is the eternal.

Then Han writes: “In contrast, the vita contemplativa is not, according to Arendt, persisting and lasting in time, but the experience of the eternal, which transcends both time and the surrounding world.” (idem page 145).

Arendt admires Socrates, writes Han, “who voluntarily renounces immortality” (pg. 146) and thus remembers that even writing becomes vita activa, and creates a temporary immortality, which Han remembers that Arendt also sought when writing.

But it is not a question of abandoning the complement of the vita contemplativa which is the vita activa, what happens is that the “animal laborans” (as Arendt calls the modern one): “is ruining all human capacities, especially action” (Han, 2023, p. 149).

Remember that the capacity for action arises from thought “which is not irrelevant to the human future, because if we considered the different activities of the Vita activa [active life] in relation to the question of which of them would be the most active and in which of them the experience of the active being would be expressed in a purer way, then the result would be that thought all activities with regard to pure active being” (Han, 2023, pgs. 149-150).

So it is not from our outside that our bad actions come from, but rather they are inside us.

Han, B.-C. (2023). Vita contemplativa. Trans. Lucas Machado. Brazil, Petrópolis: Ed. Vozes.

Essence and linguistic turn

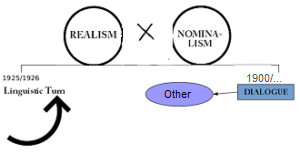

The dualism present today in human and social relations, conceives the essence only as an analogy to Being, and this was lost in the Thomistic doctrine, becoming an onto-theology until the 20th century, that is, a theological vision that only has a dual relationship with the social being, only with the varied linguistics and phenomenology and with the reunion of the Other, non-Being is resumed not as a contradiction, but as the essence of Being.

social relations, conceives the essence only as an analogy to Being, and this was lost in the Thomistic doctrine, becoming an onto-theology until the 20th century, that is, a theological vision that only has a dual relationship with the social being, only with the varied linguistics and phenomenology and with the reunion of the Other, non-Being is resumed not as a contradiction, but as the essence of Being.

The long discussion of the medieval period between realists and nominalists was based on a term little known today which was quiddity, which means that the thing the thing is, from the Greek hylé to the modern models of Heidegger’s metaphysics, where the thing that can be material or not, which was already thought along the lines of Husserl, his predecessor and teacher, who states that there is only consciousness of something, or of the thing.

There was a philosopher in the Middle Ages, Duns Scotto (1266-1308) who did not distinguish between the thing that exists (si est) and what it is (quid est), and theologically it was complicated because the thesis of Thomas Aquinas (1225 -1274) was by analogy, that is, the meaning of similarity between things or facts (Houaiss dictionary, 2009, p. 117), and religious people were always careful because in the 20th century Duns Scotto was accepted within Catholic Christian doctrine, making —he was blessed (John Paul II declared him).

Although called a moderate realist, he was already, in a way, a linguist and a precursor of the linguistic shift, also William of Ockham, his disciples worked on the issue of language, with the famous theme called Ockham’s Razor, more than simplifying the use of language as a way of overcoming the nominalism/realism dualism.

Scotto’s theory of knowledge, behind known distinctions distinctio realis (real distinction) and exists between two beings of nature, and the distinctio rationalis (distinction of reason) that occurs between two beings, but in the mind of the subject who knows, but breaks dualism by creating a third possibility, distinctio formalis (formal distinction), which occurs in the perceived entity and is neither real nor in the mind.

So in addition to his disciple William of Ockham, famous for the simplification principle called Ockham’s Razor, but in a way Descartes, Leibniz, Hobbes and Kant had their influence.

In times of pandemic, the fraternity of helping victims was much more important than the still uncertain debate about science and “beliefs” that this or that procedure is right, in hostile environments death was the winner, so dogmatists and authoritarians only got in the way, but this too was lost.

Thus, it is essential to regain awareness of the Being that we keep the Other in mind, without him, his essence and how he is for each man is neglected.

The being is important to turning the essence and new realism non dualism.

War and the illusion of power

Whatever form we define with power, and this does not exclude the empowerment of the weak, it is always a form of domination of one being over another, there would then be some form of balance, or in the words of philosophy, some form of symmetry or horizontality ?

does not exclude the empowerment of the weak, it is always a form of domination of one being over another, there would then be some form of balance, or in the words of philosophy, some form of symmetry or horizontality ?

Byung-Chul Han’s answer in the book In the Swarm seems direct and simple: respect, all other forms, presuppose some hierarchy or asymmetry of power.

It is sad to note that many contemporary philosophies and spiritualities also point to forms of power: be more, be first, how to achieve things ahead of others and thousands of “magical” ways to deceive and deceive innocent people who embark on these false promises.

We are finite and limited beings, balance and social life depend on everyone, and hatred and wars are the cruelest manifestation of forms of imbalance and asymmetry.

Egalitarianism is also an illusion, we are different and with different skills and this does not harm us, human complementarity helps us to carry out different tasks and in different contexts, some with more talent and others with more difficulties, but there is no need to discard anyone, social life is made up of a set of individual actions.

However, the set of values and stimuli that we have internally depend on a human and spiritual asceticism, not an idealistic altruism, but a good sense of respect and dignity of which we are all bearers.

Modern society, since the Enlightenment and idealism, has decided that these “subjective” factors (in fact, human interiority, real and imaginary) should be discarded, and the result is a violent society, without balance and which depends on brute force to balance, in this the State and the police force end up playing a preponderant role.

It is a shame to opt for non-violence, respect for others and moral values, all of this seems harsh and seems to restrict freedom, but it is a guarantee of balance and serenity.

In the Bible, the disciples said to the master Jesus: “your words are harsh” (John 6:60) and He replied: “this causes you to stumble”, “the Spirit is what gives life, the flesh is of no use” and some decided not to walk more with Him, what we put in our minds is what guides our life.

Clearing and being-in-the-world

A superficial reading of ontology is one that imagines being as pure contemplation or what is worse as an insurmountable human condition. Hannah Arendt’s reading of the Human Condition says something else: it concerns the conditions that man imposes on himself to survive, that which can supply man’s existence and which is not only linked to his materiality.

imagines being as pure contemplation or what is worse as an insurmountable human condition. Hannah Arendt’s reading of the Human Condition says something else: it concerns the conditions that man imposes on himself to survive, that which can supply man’s existence and which is not only linked to his materiality.

His tutor and from whom he was greatly influenced, Martin Heidegger states that being-in-the-world is a being in a certain temporal situation (hence Being and Time), but that it must always be open to becoming something new, giving life is an existential characteristic, but as a second trait, not as an essence as in materialist or nihilist ontology.

By systematizing the human condition into three aspects: labor, work and action, Arendt separates each one in a particular way: labor is linked to the biological process of human life, work is the activity of transforming natural things into artificial ones, for example, we remove the wood of the tree to build beds, cabinets, tables, etc. and finally action synthesizes our social activities and they ultimately reflect how we conceive this life.

Thus Hannah Arendt will divide human life into Vita Contemplativa and Vida Activa, a theme also explored and synthesized from the point of view of philosophical ideas by Byung-Chul Han.

So much labor, work and action are fused in what becomes our Active Life, we dealt in the previous post with the criteria of efficiency and productivity that this life reached in Modernity and its questioning, however the contemplative life is complementary to this, only in the reasoning of antiquity classicism and that modernity has explored, is that we dismiss the contemplative life as something unnecessary or even fanciful.

In Socrates’ reasoning, if man is only for eating, sleeping, having sex, then he is not a man, but an animal, from which Aristotle’s shallow reasoning comes: man is a political or social animal, that is not what characterizes Aristotle’s Zoe, is the fact that he is just an animal.

Heidegger’s clearing, therefore, is not just the possibility of man finding his Being, what he is in the world from an existential point of view, it is also finding the clearing and in it the new being, which lives in the light and not in the darkness, it is the Plato’s cave now under the gaze of a dark cloud that shakes humanity in modernity.

Thus, glory, light and truth only shine within contemplation, not only that of great mystics and sages, but of those who humbly open themselves to the new, to the light.

The limits of logical thinking

The full development of modern science and technology was the realization of a program dreamed of by Francis Bacon, René Descartes and Immanuel Kant as a total domination of man over nature on a dangerous ethical threshold, manufacturing what is natural, but this comes up against two dilemmas: the natural was and (in my opinion) will always be the “unmanufactured” and by making the substance manipulable it continues to be in fact what it was naturally.

technology was the realization of a program dreamed of by Francis Bacon, René Descartes and Immanuel Kant as a total domination of man over nature on a dangerous ethical threshold, manufacturing what is natural, but this comes up against two dilemmas: the natural was and (in my opinion) will always be the “unmanufactured” and by making the substance manipulable it continues to be in fact what it was naturally.

In excerpts from Heidegger’s notes between 1936 and 1946 (therefore in the final stage of the 2nd world war), the author wrote an essay called Overcoming Metaphysics, and with all his genius describes what would result in the technical and industrial production of life, wrote: “Since man is the most important raw material, one can count on the fact that, based on current chemical research [of course at the time], factories for the artificial production of human material will one day be installed. The research of the chemist Kuhn, distinguishing from planned directing the production of male and female living beings, according to their respective demands” (Heidegger, Uberwindung der Metaphysik, paragraph 26).

Adono and Horkheimer also expressed in the famous Dialectic of Enlightenment, that this “has always, in the most comprehensive sense of thought in progress, pursued the goal of removing fear from man and establishing him as master. However, the completely enlightened earth sparkles under the sign of triumphal misfortune.” (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1987, p. 25).

Habermas also spoke of this extravaganza of bad science fiction, experimental production of embryos, even a convinced atheist, in his work “Die Zukunft der menschlichen Natur. Auf dem Weg zu einer liberalen Eugenik?” complains about this vision of “partners in evolution” or even “playing God” as metaphors for the self-transformation of the species.

It is not about opposing the advancement of science, a retrograde thought present in all social circles, but about opposing bad science, bad progress that result in scourges for humanity itself.

The sense of fully recovering life, of opposing growing authoritarianism and warmongering, of proclaiming peace, sustainable development and the divine origin of human life is not just a proclamation of faith or serious and sincere humanism, it is a resistance of spirit, hope and a rationality above instrumental and agnostic logic.