Arquivo para February 18th, 2025

What is the Good?

This is the question that Aristotle begins to develop in his ethics (The Nicomachean Ethics): “It is generally admitted that every art and every investigation, as well as every action and every choice, have some good in view; and for this reason it has been said, with great accuracy, that the good is that to which all things tend” Aristotle (1991, p. 2).

to develop in his ethics (The Nicomachean Ethics): “It is generally admitted that every art and every investigation, as well as every action and every choice, have some good in view; and for this reason it has been said, with great accuracy, that the good is that to which all things tend” Aristotle (1991, p. 2).

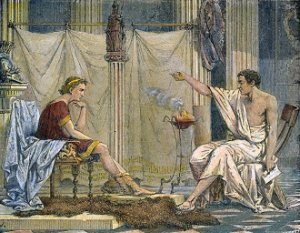

Plato’s idea of the Highest Good, which is closer to an idea of the divinity of the “World of Ideas” (he divided the world into the sensible world and the world of ideas) and Aristotle’s idea of the Good, as the idea of a choice in both art and research, presuppose that this was the choice for the social and political life of the Greek polis, which would lead to the balance of politics.

This was in contrast to the world of the sophists, where all logic and choice was for power and the possession of earthly goods, so Aristotle indicates that when he talks about ethics, he is talking about human ethics.

The author reminds us that both he and Plato established themselves on principles and were not subject to mere rhetoric and the justifications of power: “Plato had raised this question, asking, as he used to do: ‘Does our path start from first principles or does it lead towards them?’ (Aristotle, 1991, p. 5).

It is this loss of principles, and the relativism that results from it, that causes contemporary thought to lose its way about what the Good is and even what happiness is. Both Plato and Aristotle don’t lose sight of it, but they know that happiness depends on life in the polis.

Thomas Aquinas in the early Middle Ages did not define the good, but he knew that it also started from principles or what he called “primary notions”, he says: “since the good moves desire, we describe it in this way as everything that desires” and as such it can approach the good or distance itself from it.

When we see the good in this way, we can use an Aristotelian and Thomist category of seeing the good as a final cause, as a perfection to be attained.

Love for our brothers and sisters, universal brotherhood, is not a “theory”, but an end to be achieved.

*In Aristotle, causes are: material: what makes up the object or being, formal: the physical and conceptual form of the object or being, efficient cause: what makes the object or being, and final cause: what the object or being is for.

Aristotle. Ética a Nicomaco (Nicomachean Ethics). translated by Leonel Vallandro and Gerd Bornheim, Brazil: NOVA CULTURAL 1991 (Coleção os Pensadores).