Domestic life and its asceticism

I recall that the word economy also comes from oikonomia, which means “house” or “domicile”, which means “rule” or “administration”, so administering the house is the origin.

“house” or “domicile”, which means “rule” or “administration”, so administering the house is the origin.

We are reminded of Heidegger’s clearing and Sloterdijk’s treatment of it also in the sense of theory: “a kind of domestic leisure in its old definitions resembles a serene look out of the window: it is above all a matter of contemplation” (Sloterdijk, 2000, p. 37).

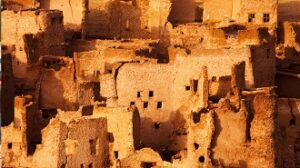

Thus, the windows would be glimpses of the houses in the walls (in the photo primitive houses in the rocks), behind which people can think and dream, and he adds: “even walks, in which movement and reflection merge, are derived from domestic life.

But since domestic life gives rise to the clearing, Sloterdijk explains: “we are only touching on the most harmless aspect of the humanization of houses. The clearing is both a battlefield and a place of decision and selection … one must decide what the men who inhabit them will become; one decides, in fact and by deeds, what kind of house builders will come to command” (Sloterdijk, 2000, p. 37) and this is why there are battles.

He then turns to Nietzsche, in the third part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, under the title “Of the diminishing virtue”, who sees houses as these environments that mean modestly embracing a small happiness and calls it “resignation”, “virtue is for them that which makes modest and domesticated: with it they make a dog of the wolf, and of men themselves the best domestic animals for men” (Nietszche apud Sloterijk, 2000, p. 49).

It should be remembered that Nietszche came from a Lutheran family and a pietist mother who had a profound impact on him.

So it could be said that Nietszche was the first to deal with “domestication” and, as Sloterdijk observes, “he read Darwin and St. Paul with the same attention and sees the school as another environment for human domestication, ‘a second horizon, this one darker’” (p. 40). 40), and Sloterdijk himself has a diagnosis that it is “likely that Nietzsche had gone a little too far in propagating the suggestion that the transformation of man into a domestic animal was the premeditated work of a pastoral association of breeders, that is, a project of the clergy…” (p. 42).

I saw a documentation by Carl Sagan famous for the Cosmos series talking about the richness and universe of a library, and Sloterdijk says that this was not just a question of an “alphabet”, “reading (lesen) had an immense power of human formation – and, in more modest dimensions, still does; selection (auslesen) however – however it was carried out – has always functioned as the eminence the brown eminence behind power” (Sloterdijk, 2000, p. 43).

Thus, lesson and selection, close words in German, play a fundamental role in the formation of the “home”, of cohabitation, and knowing how to read and write has played a central role in today’s culture, and Plato’s reflections on education and the state “are part of the pastoral folklore of Europeans”.

It will only be by rediscovering the domestic environment (the oikos) that we will find a way out of this civilization crisis.

Sloterdijk, P. (2000) Regras para o parque humano: uma resposta à carta de Heidegger sobre o humanismo. Trad. José Oscar de Almeida Marques. Brazil, São Paulo: Estação liberdade.