Being (the thing), substance and unity

Since Parmenides, Being is and non-being is not. Enlightenment/idealist philosophy conceived of the world according to the logic of Being and being, but as separate things, and this went on throughout the High Middle Ages with Porphyry, Boethius and his quarrel about universals, arriving at nominalism vs. realism at the end of the Middle Ages.

philosophy conceived of the world according to the logic of Being and being, but as separate things, and this went on throughout the High Middle Ages with Porphyry, Boethius and his quarrel about universals, arriving at nominalism vs. realism at the end of the Middle Ages.

Some readers of classical antiquity may notice that Parmenides’ philosophy refers to nature, which he proposes as a single, eternal, immutable and indivisible being, but denies the vision of a constantly changing reality with its plurality. Karl Popper’s book “Parmenides’ World: Essays on Pre-Socratic Enlightenment” is very clarifying.

In addition to Leibniz’s monism, it can be either idealist dualism or pluralism, which affirm the existence of two opposing or distinct and irreconcilable realities, such as mind and matter.

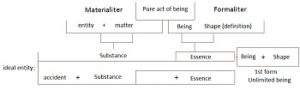

But at the heart of this contradiction is the idea of what the thing (the quid) and the substance are.

Suzanne Mansion (1916-1981), a Belgian specialist in Aristotle, restates this debate in the following current terms: let’s ask ourselves the following question: how can we understand quidity ? can we define it as a specific way of being, or rather of “being a thing” ? she explains that this expression has the Greek correlative Tó Ti en Einai*, which the Latins translated as quod quid erat esse, or quidditas (*τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι significa “o que era para ser” ou “a essência”).

This quidditas allows us to interpret what a thing is, was and is becoming (taking into account the verb tenses), which creates a dimension of temporality proper to the being – to the Tó Ón – as it exists in act, as an being subject to the changes that occur in the world, in the background and to becoming, with a clear reference to Thomas Aquinas’ way of conceiving the being (Mansion, 1984).

Thomas Aquinas was a realist, but another moderate realist of his time was Duns Scotus, who argued that universality (Boethius’ theme, universal vs. particular), for him the concept of being as being, that is, the purest and most general concept of being, is “transcendental” (not that of idealism, which did not exist at the time, but the Greek eidos).

It is beyond any categorization and can be applied both to created things and to the Creator, thus overcoming the dualism of body and mind, or substance and being.

Of course this is a linguistic turn, Scotus was once seen as a nominalist, but today in the contemporary concept he is a moderate realist according to various classifications.

What does this have to do with unity, everything, those who separate the vita activa from the vita contemplativa, those who see the world as action in constant change, without the contemplation that allows us to see the essence of the entity, a flower may disappear, but its essence remains in both the poetic and realistic sense, without the flowers there is no fruit.

The world of action, of pure “being” separated from its essence, is in fact non-being, while the non-being that implies the oriental “absence” (see our posts on the concept in Chul-Han) and the stopping of productivism, consumerism and the efficiency of the Society of Tiredness, is a Being-Living, the modern the activism, or Rancière’s critique of engagement in art.

Unity lies in combining these two concepts in their triad of the third included and the one.

Mansion, Suzanne (1984). Etudes aristotéliciennes: recueil d’articles. Louvain-la-Neuve: Edited by J. Follon.