Posts Tagged ‘Deus’

Bad religion and the virtues

Contemporary philosophy oscillates between definitions of ethics and morality, with morality seen as a reduction to the morality of customs, lacking a depth of virtues and true religiosity.

definitions of ethics and morality, with morality seen as a reduction to the morality of customs, lacking a depth of virtues and true religiosity.

The three theological virtues have been lost: faith, hope and charity, which must be “infused” by God, are confused with the religiosity of fortune-tellers and material goods, hope becomes a kind of positive thinking and behavioral feelings animated by some “coach” and charity, some superficial kindness such as pity, mercy and social aid.

The so-called cardinal virtues are prudence, run over by a world driven by impulses, justice which has become pure political manipulation, fortitude confused with physical or political strength and temperance present in very few situations and people, we live in times of anger.

A rare contemporary philosopher to deal with the subject was Philippa Foot, who died in 2010 at the age of 90. Despite her name, she was British and responsible for the resurgence of “virtue ethics”.

Foot did not abandon the classics, but re-read them for modern times. She believed that morality should be understood in terms of virtues of character, rather than just rules and consequences of actions.

Among her works, she modernized Aristotle’s ethical theory (Nicomachean Ethics) into a contemporary view of the world, showing that it can compete with popular theories such as deontological ethics and utilitarian ethics (that focused on goods, for example, present in religions).

She elaborated and discussed the so-called Tram dilemma (Foot, 1978, see figure), also addressed by other contemporary philosophers such as the famous John Rahls, also extensively analyzed by Judith Jarvis Thomson and more recently by Peter Unger.

The dilemma is simple: the valet must analyze the “lesser evil” where on one line he would run over one person and on another several, in a streetcar that is out of control and cannot stop.

The hope variant is a version of the dilemma considered by Daniel Zubiria, where there is a 50% chance of the derailed train saving all the people and not opting for either track, a similar argument is that of Jonah Barnaby.

The problem is interesting because it necessarily falls into the theological virtues.

Regarding faith, there is only one possible argument: prayer, which is inalienable from religious thought, it is not an exercise in rhetoric, logical and emotional maneuvers, it must be based exclusively on the relationship with God, so the utilitarian or deontological relationship is dispensable since it is theo-ontological: “my Father’s house is a house of prayer” (Lk 19,46).

Philippa Foot, (1978) The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of the Double Effect in Virtues and Vices. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

The difference of the divine Love

Hannah Arendt’s reading of Saint Augustine in her doctoral thesis remains between these two interpretations of human and divine love.

in her doctoral thesis remains between these two interpretations of human and divine love.

To analyze this, Arendt interprets Augustine’s work as governed by three principles that appear without apparent contradiction. She increased Augustine’s dogmatic rigidity to the extent that Christianity was inserted into his thinking, this consisting of his passage from pre-theological, philosophical thinking to theological thinking, according to the author.

Thus the first part of the author’s thesis, entitled “Love as desire: the anticipated future”, approaches love from a philosophical perspective of continuity with Hellenic thought, in which love is seen as a disposition that is always driven by lack, by something that is not possessed, but which one hopes to have, as a means of achieving happiness, thus desire is something not yet achieved while Love is the desire obtained, and this is philosophical.

These two types of love are given two names by Augustine: caritas and cupiditas. They differ in their love for the object they love, “but both right and wrong love (caritas and cupiditas) have this in common – desirous longing, that is, appetitus”, writes the author.

Caritas is pure, true love, because it desires God, eternity and the absolute future, while cupiditas loves the world, the things of the world, here it is pre-theological, because charity is not just a passing love, or desire for a passing good, but for the eternal.

Whether we are religious or not, we are between desire and possession, after we have obtained the desired object in general, and enjoyed the pleasure of this possession, cupiditas passes and something eternal remains if there is caritas in it, that is an Eternal Love, which gives an eternal possession and then does not pass away.

So the man who has this quest must withdraw into himself, and within himself, isolating himself from the world, he penetrates the Augustinian “quaestio”, the guiding thread that Arendt pursues: “for the more he withdrew into himself and collected himself in the dispersion and distraction of the world, the more he became a ‘question for himself’,” wrote the author.

Every philosophy has a basic question, and Augustine’s becomes theological: “What do I love when I love my God?” (Confessions X, 7, 11 apud Arendt p. 25), even if it is “in the world”.

Thus the second part of her thesis is called “and ‘Creature and Creator: the remembered past’, in book X of Confessions. “Memory, then, opens the way to a transmundane past as the original source of the very notion of a happy life,” the author wrote about Augustine.

In proposing a relationship with the Creator, man does not lose himself, but finds himself, and this is different from any kind of worldly attachment, the god of money, consumption or desire.

Arendt, Hannah. (1996) Love and Saint Augustine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Joy, sacrifice and hope

Pain is part of human reality, and so no joy is everlasting if it doesn’t understand sacrifice, in the etymology of the word “sacred office”, it’s not exactly pain, as Byung-Chul Han describes in The Palliative Society: pain today, meaningless pain, it’s “bodily affliction”, pain has become a thing, it has lost an ontological and in a way “eschatological” meaning, “meaningless pain is possible only in a bare life emptied of meaning, which no longer narrates”. (Han, 2021, p. 46).

everlasting if it doesn’t understand sacrifice, in the etymology of the word “sacred office”, it’s not exactly pain, as Byung-Chul Han describes in The Palliative Society: pain today, meaningless pain, it’s “bodily affliction”, pain has become a thing, it has lost an ontological and in a way “eschatological” meaning, “meaningless pain is possible only in a bare life emptied of meaning, which no longer narrates”. (Han, 2021, p. 46).

Han cites literary authors such as Paul Valéry, for whom in his book Monsieur Teste “is silent in the face of pain. Pain robs him of speech” (Han, 2021, p. 43), and also Freud, for whom ”pain is a symptom that indicates a blockage in a person’s history. The patient, because of his blockage, is unable to move forward in the story” (p. 45).

It is with the Christian mystic Teresa of Avila, as a kind of counterfigure of pain, “in her, pain is extremely eloquent. The narrative begins with pain. The Christian narrative verbalizes pain and also transforms the body of the mystic into a stage … deepens the relationship with God … produces intimacy, an intensity” (p. 44). For those who don’t know, it was through reading this book that the philosopher Edith Stein, a disciple of Husserl like Heidegger, converted to Christianity.

Sacrifice is the art of living joyfully through pain. Of course, it’s a mistake to think about and desire pain, but if it comes, and someday it will, it can be re-signified as a “sacred office” that is offered. Byung-Chul Han wrote about it: “Suffering is not a symptom, nor is it a diagnosis, but a very complex human experience.” Only great mystics have penetrated it.

In Mark’s Gospel (Mk 9:31), Jesus shocks his disciples by teaching them in secret: “And he said to them, ”The Son of Man is going to be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him. But three days after his death he will rise again,” and then he denies all forms of human power: ‘Whoever wants to be first, let him be servant of all,’ and finally he teaches the simplicity of children: ‘Whoever welcomes one of these children welcomes me,’ is different from what they think today.

Understanding pain, the inverted logic of power and the simplicity and innocence of children is a distant logic in a civilization in crisis, hedonistic, authoritarian and full of malice.

Han, B-C. (2021) A Sociedade paliativa: a dor hoje. Transl. Lucas Machado, Brazil, Petrópolis: ed. Vozes.

The sky can speak

Sloterdijk assumes the time that through the ages men “made gods speak”, this is also what he says about the “speech” of Jesus, and he says with historical propriety: “Finally, those who were invoked too much also made themselves known through the personal incarnation: sometimes they took the liberty of resorting to apparent bodies that came and went as they pleased.” (pg. 22), it is true and this means: Do not use God’s name in vain.

ages men “made gods speak”, this is also what he says about the “speech” of Jesus, and he says with historical propriety: “Finally, those who were invoked too much also made themselves known through the personal incarnation: sometimes they took the liberty of resorting to apparent bodies that came and went as they pleased.” (pg. 22), it is true and this means: Do not use God’s name in vain.

But historical reasoning helps better with the other alternative use of “God”: “… or they were condensed, “in the fullness of time”, into a Son of Man, into a saving Messiah. After Cyrus II, the king of the Persians famous for his religious tolerance, allowed the Jews who had been taken captive to Babylon to return to Palestine in 539 BC, putting an end to an exile of almost sixty years… The spiritual elite of the Jews became much more receptive to messianic good news — Second Isaiah set the tone for this.” (p. 22).

He correctly says when he calls Cyrus “panegyric” (worship of an abstract god), he did not convert or even abandon his beliefs in other gods, as “an instrument of God” he freed a people, the author also recalls Marcião who worshiped “the unknown god” that will make Paul call the Greeks a religious people, but states that the known God is the one that the apostle of the Gentiles (Paul) proclaims in the figure of Jesus, the Redeemer.

The issue of redemption pointed out by Sloterdijk from a historical point of view, has its meaning as these are moments in which “heaven opened”, but he sees it as a spectacle where “The oldest stage of evidence from sensitive and supersensitive sources is shown in the form of commotion of the participants generated by a “spectacle”, a solemn rite, a fascinating hecatomb.” (pg. 24) and this has been repeated throughout the ages, with great speakers and great “media experts”, but this will be the true God, of Augustine as Sloterdijk himself cites him (De vera religione).

He is also right when he says about some who consider themselves to have “divine” gifts: “. In general, it was assumed that there were interpreters capable of associating a practical meaning with the encoded symbols” (pg. 25), but again not these false oracles that seek spotlight.

See how Jesus asks for the healing of a man born deaf/mute (Mc 7,34-36): “Looking at the sky, he sighed and said: “Ephphatah!”, which means: “Open up!” Immediately his ears opened, his tongue loosened, and he began to speak without difficulty. Jesus insistently recommended that they not tell anyone. But, the more he recommended, the more they disclosed”, this small detail that appears in many miracles, do not disclose, that is, it is not a spectacle, it does not mean not doing it well, however, with a sacred sense.

The meaning of this cure is deeper, in addition to making a world deaf from birth hear and speak, reading previous excerpts from the evangelist Mark we find the absurd idea (present in today’s “religious” circles), using the idea of a Syro-Phoenician woman whose daughter had a “demon”, it is not the idea that an illness or some bad occurrence is “punishment from heaven”, as it is from the heart of man that “impure” things come out: evil, greed, etc.

The Ephphatah (open sky) said to cure a deaf-mute from birth is because it is not a common disease, someone whose life and cognitive system were not taught to listen and speak, did so immediately, it´s complex.

In dark times, it is necessary for the deaf to hear and the mute to speak, as there are those who want to remain silent.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024). Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

The universe was created

Whether or not the hypothesis of the creation of the universe by the Big Bang is valid (there is the hypothesis of the multiverse) at some point it appeared, Heidegger’s category of dasein being there is very expensive, but this is essentially the human of Being.

of the universe by the Big Bang is valid (there is the hypothesis of the multiverse) at some point it appeared, Heidegger’s category of dasein being there is very expensive, but this is essentially the human of Being.

Sloterdijk goes into this merit by writing: “Three hundred years after the death of the man who was venerated by his followers as the arrived Messiah, the Council of Nicaea established the dogma that the Lord Jesus Christ would be God of God and light of light, true God of the true God, begotten and uncreated—whatever that means.” (pg. 31), if the name of God bothers (and makes sense), creation was not created.

Recent photos from the James Webb Telescope intrigue scientists because apparently there was no slow creation, entire complex galaxies seem to be at the beginning of the Big Bang, and the force that moves them seems to be something truly extraordinary, unthought of by science.

As we said in the previous post, in addition to Jesus, for Sloterdijk also Socrates and Seneca must be examined, and they are historically close, he wrote: “What in common language is called “becoming human” designates, discounting extrapolations, a state of things that the Roman philosopher Seneca (1-65 BC), partly a contemporary of Jesus (4 BC-30 BC), for some time mentor of the young Nero [see] and, later, forced by him to commit suicide, revealed in the following sentence: sine missione nascimur — meaning: we were born with the certain prospect of dying” (pgs. 31-32).

Thus, one could separate the mortal from the important, but Sloterdijk thinks differently and writes: “Everyday levity is a mask for the timeless ghost of indestructibility; the preacher in Palestine and the philosopher in Rome take off this mask to testify that there is something indestructible that is not of a frivolous and phantasmatic nature.” (pg. 33), hence his disbelief in something “indestructible”, and the difference from the messianic preacher of Palestine is “resurrected”.

For him, Jesus distinguished himself in speaking: “but perhaps also just a fazn de parler [way of speaking] for “I” —, he came into the world, as he himself was led to say, to sign his teaching with his life.” (pg. 33), but his life was different as someone who came from another reality and knew it.

Thus he is trapped in seeing human realities as “ex machina”: “The man who called himself “Son of Man” spoke essential elements of his message from the cross, in which he ended up as deus fixus ad machinam [god stuck to the machine]” (pg. 33), but it is not, he will examine the writings of Ignatius of Loyola (founder of the Jesuits) and Hegel, but he is stuck with Hegel’s notion of absolute, because he does not admit the universe complex that we now see through James Webb.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024). Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

The historical analysis of theopoetry

No one will be converted by reading Sloterdijk, he calls the term religion “nefarious”, but the term not the culture he seeks to delve into, about the term he states: “… especially since Tertullian reversed, in his Apologeticum (197), the expressions “superstition (superstitio)” and “religion (religio)” against Roman linguistic usage: he called the traditional religion of the Romans superstition, while Christianity should be called “the true religion of the true god”. In this way, he produced the model for the Augustinian treatise De vera religione [On true religion] (390), which marked an epoch, through which Christianity definitively appropriated the Roman concept” (pg. 20) and its reasoning and historical vision is much more accurate than the one that wants to appear as if Constantine created a “religion”.

he calls the term religion “nefarious”, but the term not the culture he seeks to delve into, about the term he states: “… especially since Tertullian reversed, in his Apologeticum (197), the expressions “superstition (superstitio)” and “religion (religio)” against Roman linguistic usage: he called the traditional religion of the Romans superstition, while Christianity should be called “the true religion of the true god”. In this way, he produced the model for the Augustinian treatise De vera religione [On true religion] (390), which marked an epoch, through which Christianity definitively appropriated the Roman concept” (pg. 20) and its reasoning and historical vision is much more accurate than the one that wants to appear as if Constantine created a “religion”.

Historical because the influence on Augustine of the Neoplatonists, especially Plotinus, is not only reasonable, but strong enough for what he will write, not in Vera religione, but in his Confessions, which is practically his testament and model of his conversion, Augustine leaves Manichaeism (two opposing poles in dispute) to discover the One (Plotinus’ category), the religion of Love, which earned Hannah Arendt a doctoral thesis.

However, the political action of religion is not denied, Sloterdijk writes, citing Virgil’s Aeneid: “No imperialism rises without the current positions of the constellations in the temporal sky being interpreted, both in the case of those in power and those aspiring to it. Added to them are advice from the underworld: “Tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento.” (pg. 26 quoting Virgil). In the figure above, Euripides’ representation of Medea from deus ex machina.

He is talking about cultural communities and quotes Constantine: “the symbolic or “religious” and emotional integration of larger units: of ethnicities, cities, empires and supra-ethnic cultural communities — the latter of which could also assume a metapolitical, or rather, anti-political character, as was clear in the case of Christian communities in the pre-Constantinian centuries” (pg. 25-26), when Christians were persecuted and this is history.

The church was already structured at this time: “The bishops (episcopoi: supervisors) were, in essence, something like praefecti (commanders, procurators) in religious attire; its dioceses (in Greek: dioikesis, administration) they resembled the previous imperial districts after the new subdivision made by Diocletius around the year 300; above all through them, the principle of hierarchy reached the ecclesiastical organization in formation…” (pg. 26), thus Constantine in 313 when he places the Catholic religion as the “official” religion [through the influence of his mother Helena] had little or almost no influence its structure.

In fact, in the Jewish heritage, it had already enshrined many rituals: “The mediological principle apò mechanès theós, in fact, deus ex machina, typical of scenic technique or religious dramaturgy, was in fact already in use in several Near Eastern rituals long before to emerge in the Athenian theater” (pg. 28), thus this “deus ex machina” was already present in Judaism.

The author recognizes the religious turn of Jesus: “The god-man, who called himself “Son of Man” inspired by Persian and Jewish sources — possibly a messianic title, but perhaps also just a fazn de parler [way of speaking] to “I” —, came into the world, as he himself was led to say, to sign his teaching with his life” (pg. 32), although he compares him with Socrates and Seneca who had “indispensable convictions”.

Sloterdijk, P. (2024) Fazendo o céu falando; a teopoesia (Making the sky speak: on theopoetry), Trans. Nélio Schneider, Brazil, São Paulo: ed. Estação Liberdade.

Sloterdijk’s theopoetry

One of the greatest contemporary philosophers, of enormous influence on Byung-Chul Han, Sloterdijk is far from being a Christian or any type of religious person, but he is wise enough to know the enormous influence of religion on culture throughout the centuries and in our time.

of enormous influence on Byung-Chul Han, Sloterdijk is far from being a Christian or any type of religious person, but he is wise enough to know the enormous influence of religion on culture throughout the centuries and in our time.

What sky is he talking about then, he clarifies: “The sky we are talking about is not an object capable of visual perception. However, since time immemorial, when looking up, representations in the form of images accompanied by vocal phenomena were imposed: the tent, the cave, the vault; in the tent the voices of everyday life resound, the walls of the caves echo ancient songs of magic, in the dome chants in honor of the Lord in the heights reverberate” (p. 11), explains the author in your preliminary observation.

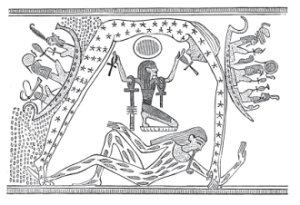

Mythological gods, the author based on the Greenfield papyrus (10th century BC), where we see: “Detail from the Greenfield papyrus (10th century BC)”: “The goddess of the sky, Nut, bows over the god of the earth, Geb (lying down), and of the god of the air, Shu (kneeling). Egyptian representation of heaven and earth” (p. 12, photo, Wikipedia Commons).

However, it is not a mythological essay either, he writes: “What we intend, in what follows, is to speak of communicative, luminous skies that invite raptures, because, corresponding to the task of poetological enlightenment, they constitute zones of common origin of gods, verses and pleasures” (p. 13).

It makes a curious metaphor with Mt 13:34, a passage so dear to Christians that says: “All this Jesus spoke in parables to the crowds. He spoke nothing to them without using parables, to fulfill what was said by the prophet: ‘I will open my mouth to speak in parables; I will proclaim things hidden since the creation of the world'” (Mt 13,34-35), it was necessary because it spoke of “communicative, luminous” heavens.

In his metaphor Sloterdijk says: “Deus ex machina, deus ex cathedra and without parables he told them nothing” (p. 13, about divine reality), and here the philosopher questions the contemporary world, which idolizes these contemporary gods ex machina and ex cathedra.

It will remind you of the theopoetry in the mouth of Homer, who had “speaking gods”, but it will also remind you of the passage in which Zeus rebukes “the willful manifestations of his daughter Athena”, and says to her: “My daughter, what word has escaped you from the barrier teeth?” (p. 15)

Of course, as Christians we do not talk about mythological gods, it reminds us of Christian semiotics where signs are important: “the zone of signs grows parallel to the art of interpretation. The fact that it is not accessible to everyone is explained by its semi-esoteric nature: Jesus already reproached his disciples for not understanding the “signs of the time” (semaîa tòn kairòn).” (pg. 25).

It is not about delusion or gross falsehoods about eschatological events, if they exist they are only bearers of these “signs” true oracles and prophets, or to use Sloterdijk’s term: theopoets who say things from heaven, such as poetry and clarity, even if use parables due to the difficulty of expressing them in everyday language and reality.

The signs of the times, dark as wars and alive as those who resist with the spirit of hope and peace, do not make tragedy like the Greeks a sign of revenge or intolerance, but of seeing beyond what the raw and naked reality seems to show.

Sloterdijk, P. Making the sky speak: on theopoetry, Trans. Nélio Schneider, Liberdade Station, 2024.

War and the illusion of power

Whatever form we define with power, and this does not exclude the empowerment of the weak, it is always a form of domination of one being over another, there would then be some form of balance, or in the words of philosophy, some form of symmetry or horizontality ?

does not exclude the empowerment of the weak, it is always a form of domination of one being over another, there would then be some form of balance, or in the words of philosophy, some form of symmetry or horizontality ?

Byung-Chul Han’s answer in the book In the Swarm seems direct and simple: respect, all other forms, presuppose some hierarchy or asymmetry of power.

It is sad to note that many contemporary philosophies and spiritualities also point to forms of power: be more, be first, how to achieve things ahead of others and thousands of “magical” ways to deceive and deceive innocent people who embark on these false promises.

We are finite and limited beings, balance and social life depend on everyone, and hatred and wars are the cruelest manifestation of forms of imbalance and asymmetry.

Egalitarianism is also an illusion, we are different and with different skills and this does not harm us, human complementarity helps us to carry out different tasks and in different contexts, some with more talent and others with more difficulties, but there is no need to discard anyone, social life is made up of a set of individual actions.

However, the set of values and stimuli that we have internally depend on a human and spiritual asceticism, not an idealistic altruism, but a good sense of respect and dignity of which we are all bearers.

Modern society, since the Enlightenment and idealism, has decided that these “subjective” factors (in fact, human interiority, real and imaginary) should be discarded, and the result is a violent society, without balance and which depends on brute force to balance, in this the State and the police force end up playing a preponderant role.

It is a shame to opt for non-violence, respect for others and moral values, all of this seems harsh and seems to restrict freedom, but it is a guarantee of balance and serenity.

In the Bible, the disciples said to the master Jesus: “your words are harsh” (John 6:60) and He replied: “this causes you to stumble”, “the Spirit is what gives life, the flesh is of no use” and some decided not to walk more with Him, what we put in our minds is what guides our life.

What is love after all

In a polarized world and now on the verge of  regional wars that can escalate, talking about love seems innocuous and has no reflection on reality, but there are good works produced by humanity.

regional wars that can escalate, talking about love seems innocuous and has no reflection on reality, but there are good works produced by humanity.

Paul Ricoeur wrote and we have already posted about this a few times about Le socius e le prochain (The partner and the neighbor), separating interests from true love for others.

However, Hannah Arendt’s work, although not definitive regarding love, the advisor Karl Jaspers himself expressed this about his doctorate “Love in Saint Augustine”, developed and appropriated some fundamental categories on the subject, of course we are not talking about erotic nor familial love.

According to author George McKenna, in a review of her thesis, Arendt tried to include a revision in her “The Human Condition”, but it is not very clear in Arendt’s book that, despite this, it has good development.

If this love can also be expressed in ancient Greek literature, such as agape love, which differs from eros and philia in this literature, from a Christian point of view the best development made is in fact that of Saint Augustine.

First because he separated this concept from good x evil Manichaeism, a dualism still present in almost all Western philosophy due to idealism and puritanism, then because he was in fact raptured upon discovering divine love, he wrote: “Late I loved you, O beauty so ancient and so young! Too late I loved you! Behold, you lived within me and I was looking for you outside!” (Confessions of Saint Augustine).

Then man must love his neighbor as God’s creation: […] man loves the world as God’s creation; in the world the creature loves the world just as God loves it. This is the realization of a self-denial in which everyone, including yourself, simultaneously reclaims your God-given importance. This achievement is love for others (ARENDT, 1996, p. 93).

Man can love his neighbor as a creation by returning to his origin: “It is only where I can be certain of my own being that I can love my neighbor in his true being, which is in his createdness.” (ARENDT, 1996, p. 95)

In this type of love, man loves the divine essence that exists in himself, in others, in the world, man “loves God in them” (ARENDT, 1996, 9

The biblical reading also summarizes the law and the Christian prophets like this (Mt 22, 38-40): “This is the greatest and the first commandment. The second is similar to this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’. All the Law and the prophets depend on these two commandments.”

Love contains all the virtues: it does not become conceited or angry, it knows how to see where the true signs of happiness, balance and hope are found, even in a troubled world.

ARENDT, Hannah. Love and Saint Augustine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

The heart and beliefs

The heart is a vital organ, it irrigates blood throughout the organism reaching all the cells of the human body, when we talk about beliefs (they are also hidden in objects of human knowledge, we believe that something is a certain “way”) we do not we just talk about faith.

throughout the organism reaching all the cells of the human body, when we talk about beliefs (they are also hidden in objects of human knowledge, we believe that something is a certain “way”) we do not we just talk about faith.

Byung-Chul Han, when carrying out his analysis based on the classic authors of Western philosophy, approaches a perspective of what he will call “affective tone”, focusing mainly on Heidegger.

His book, unlike others that are just essays, has “Heidegger’s heart: on the concept of affective tonality in Martin Heidegger” (Ed. Vozes, 2023), his first book in my opinion, with a new, human and spiritual analysis. even spiritual at the core of Western philosophy.

Part of a concept dear to Judeo-Christian civilization, which is that of circumcision, but circumcision of the heart and not of the failed organ (the skin attached to the beginning of the penis), it is necessary to remember that although it is a male organ, it is an emblem of power, of authority and desire, was culturally a warlike culture.

The part of his vision with his eastern vision and that has a spiritual sense for his entire philosophical question, Han will develop that it is the circumcision of the heart, that which modulates and governs affection, circumcision has a different meaning than what is commonly spoken, the controversy between Christians and Jews at the beginning of the Christian era, is the circumcision of the heart.

Circumcision is the act of removing the skin of the male sexual organ, but even in the biblical sense it was the skin of the heart, in Deuteronomy it reads: “Circumcise therefore the foreskin of your heart, and no longer stiffen your neck” (Dt 10,6), citing in the epigraph of the first chapter of the book: “Circumcision of the heart” (Han, 2023, p. 7).

Thus, “this circumcision frees the heart from subjective interiority” (Han, 2023, p. 11), and there is a surprising preliminary conclusion in Heidegger: “Heidegger’s heart, on the other hand [confronts with Derrida], listens to one voice , follows the tonality and gravity of the “one, the only one that unifies” (Han, 2023, p. 14-15), for him it is an “ear of his heart” and thus there is something strong spiritual in this.

It is there that the human being finds his essence: “he remains in tune with that from which his essence is determined. In the tuning determination, man is affected and called by a voice that sounds all the purer the more silently it resonates through the sonant” (Han, 2023, p. 15) literally quoting Heidegger.

He will not say that it is faith, and it reveals the Buddhist influence of his thought, the author’s only link, in my opinion, with idealism, because in Buddhism there is only a personal elevation, there is no Person on the other side, who resonates through the resounding, that voice of the Holy Spirit.

The author clarifies the disagreement between Derridá and |Heidegger: “The ‘polyphony’ that Derrida opposes to totality does not exclude tonality” (pg. 16) we would say if these authors: Han, Derrida and Heidegger were Christians, that Heidegger and Han would be monotheists and Derrida would be polytheist, but it is clear that this “resounding voice” is not that of God, but from within.

Han, B.C. (2023) Heidegger’s Heart: on the concept of affective tone in Martin Heidegger. Trans. Rafael Rodrigues Garcia, Milton Camargo Mota. Brazil, Petrópolis: Vozes.