Arquivo para October, 2024

Totalitarianism and political ontology

Wars always revolve around totalitarian governments, because they have a unilateral worldview, which despises the cultures and views of other peoples and thus wants to subject their peoples, who generally accept different cultures, to a single worldview.

Hannah Arendt faced up to these regimes in her 1951 book, “The Origins of Totalitarianism”. She was convinced that after the end of the Second World War, the problem didn’t end there; she spoke of hell, nightmares, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, onions and even the ugliness of an omelette, among many other things, when the stories of Auschwitz came into her hands.

In trying to describe the totalitarian experience, Arendt was faced with the dilemma of how this experience could not be explained, not by political philosophy or traditional concepts, not just by the culmination of a process of developing something from a past, but in what Heidegger called the “forgetting of being”.

I’m reminded of a striking phrase by Lygia Fagundes Telles, who died on April 16, 2022, on her 99th birthday: “There is no coherence to mystery or logic to absurdity.” Dictators and their narratives only have logic in systematic propaganda, and in a claque of other fanatics who support them and identify with them, in short, a partial narrative of reality.

This form of narrative that Arendt wrote was opposed by a contemporary like Voegelin, about whom she responded to her analysis: “I have not written a history of totalitarianism, but an analysis in historical terms of the elements that crystallized in totalitarianism” (ARENDT, 2007, p. 403).

He also wrote in “The Crisis of the Republic” that the first fundamental difference between totalitarianism and the other categories present in history lies in the fact that totalitarian terror “turns not only against its enemies, but also against its friends and defenders”; a second difference would be its radicalism, which makes it capable of eliminating not only the freedom of action of individuals, as tyrannies did through political isolation, eliminating not only opponents but also unreliable allies, there is a clear parallel in today’s war.

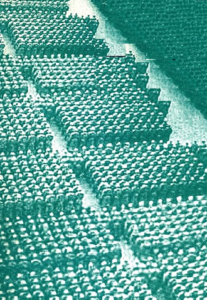

In her note number 81, Arendt wrote: “The total number of Russians killed during the four years of war is estimated at between 12 and 21 million. In a single year, Stalin exterminated some 8 million people in Ukraine alone (see Communism in action, U. S. Government, Washington, 1946, House Document no. 754, pp. 140-1).” Again, the similarity with the current war is no coincidence, and after Butcha then Mariupol had a similar drama to Gaza (photo), but there are only ideological partial narratives.

The last topic of Arendt’s book is: “Ideology and terror: a new form of government”. If you’re interested in avoiding totalitarianism, just read it. It’s likely that we’ll become aware of this terror and stop feeding it in our day-to-day lives.

Arendt, H. (2007) Origens do Totalitarismo. Trad. Roberto Raposo. Brazil, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras..

Believe in divine protection and do good

Despite the climate of war, we must wish for peace. We warned in yesterday’s post that an escalation was imminent and it has happened, the climate and hate speech on both sides in the current global polarization is advancing and only those who continue to do good will be at peace.

We warned in yesterday’s post that an escalation was imminent and it has happened, the climate and hate speech on both sides in the current global polarization is advancing and only those who continue to do good will be at peace.

It seems heroic, innocent or even childish to continue to wish for and do good, but this is the only way not to fall into the trivialization of evil, polarization and inhuman discourse.

Yesterday, on Monday night in Brazil and early Tuesday morning in Israel, more than 180 missiles from Iran were launched at Israel, hypersonic missiles that traveled in 12 minutes until they hit Jewish soil; the number of victims and targets hit were not disclosed.

The involvement of the Arab world, Turkey, Lebanon and Syria have already declared their support for the attack, which had Palestinian celebrations in Gaza, takes the confrontation to a global scale, in the United States, Biden asked the forces in the area to defend Israel, which promises retaliation to Iran.

The possibility of the closure of the Gulf of Oman will affect the price of oil worldwide and, with it, the cost of products that depend on transportation and global logistics.

Only by adhering to goodness, peace and your daily life can we remain emotionally balanced and serene, even in the face of adverse circumstances, where everyone gives in to panic, hatred and the trivialization of evil.

For the philosopher Hannah Arendt, the banality of evil is the phenomenon of our character’s refusal to reflect and the tendency not to assume the consequences of actions that do not assume the consequences of evil, and thus prevent us from adhering to the good.

We only have protection in our spirit and soul when we resist the temptation to evil, what the philosopher and educator Edgar Morin also calls “resistance of the spirit” in the midst of polarization, hatred and war; by doing good actions we attract peace around us and divine protection.

The good and political ontology

Although the philosophical discourse on the good is broad and varied, modernity has lost part of this foundation when it is linked to the question of Being. In the political dialogue, for example, the development of Hannah Arendt and her works: “The Banality of Evil” and “The Human Condition”, or Freud’s “The Evil of Civilization” or Paul Ricoeur’s “The Symbolic of Evil” do not appear.

good is broad and varied, modernity has lost part of this foundation when it is linked to the question of Being. In the political dialogue, for example, the development of Hannah Arendt and her works: “The Banality of Evil” and “The Human Condition”, or Freud’s “The Evil of Civilization” or Paul Ricoeur’s “The Symbolic of Evil” do not appear.

The latter three can rework, in tragic dimensions, what we claim is the absence of a political ontology, what Hannah Arendt seeks in her texts.

Paul Ricoeur, explaining the symbolism of evil, wrote of individual attitudes that seek to “console” the victims of evil as a causal motive:

“To people who suffer and who are so ready to accuse themselves of some unknown fault, the true pastor of souls will say: God certainly didn’t want this; I don’t know why; I don’t know why…” (Paul RICOEUR, ‘Le scandale du mal’, op. cit., p. 60), looking at the origin of an evil, which the majority cannot explain, although they feel it.

The traditional philosophical discourse on the good revolves around either utilitarianism (the good is what maximizes happiness, in Stuart Mill), deontologism (the good is acting in accordance with moral duty) and eudaimonism (the supreme good is happiness, achieved through virtue).

Kant elaborates that the supreme good is the good will, that is, acting out of duty and not inclination, and so in contemporary philosophy (with an idealist foundation) the good ranges from virtue ethics to care ethics, but the absence of foundational values on evil ends up incorporating relativism and falls into the political discourse of populism and modern sophism.

Although the Greeks touched on the ontological question, the idea of Platonism that the good is the highest form of reality, the cause of what exists and the ultimate goal of knowledge, modernity is paralyzed under the aegis of an evil that is not only structural, but that affects being: Arendt’s banality of evil and Freud’s civilizational malaise.

Arendt shows that there is a fundamentally political gap in current thinking, which falls into the category of the plurality of philosophical thought. Before Hitler’s rise, Arendt’s search went on to other philosophical questions that also went in the direction of the good. In her doctoral thesis, supervised by Karl Jaspers, she discussed “The concept of love in St. Augustine”, but then she revisited the ontological question and went on to analyze the question of totalitarianism.

On the question of Love (agape) in his doctorate, it remains unfinished, according to his own supervisor, but even if evil seems to prevail, it is the good that we must pursue and only it can free us from the historical condition where evil seems to triumph.