Arquivo para a ‘Sem categoria’ Categoria

The missing future, semi-open dialogues

The idea that we are about to change is in the mouth of many apocalyptics and until some idealist theorists and philosophers, although most claim openness and dialogue, what they think about it is not elaborate, make long speeches and weave unrealistic narratives, but they want only to hear their own voice.

of many apocalyptics and until some idealist theorists and philosophers, although most claim openness and dialogue, what they think about it is not elaborate, make long speeches and weave unrealistic narratives, but they want only to hear their own voice.

The true dialogue between tradition and change, fortunately in this field many people are doing this properly, must at the same time provide a rereading of the past, a respect and an understanding of why the events happened this way or that.

This is the reading from the pre-Socrates, through the high and low middle ages, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, although criticism can be done throughout, and even it must be well done, it is easy to do critical rereading because this time It has been difficult because the time has come.

Especially difficult for the Enlightenment and modernity, postmodernity or late, or its continuity, is still difficult to read because the transition has not taken place and the problem is the difficulty of overcoming it, almost everyone will agree that the Modernity is already more tradition than any possibility of a new “revolution” within its thinking, although the attempts are many.

Nietzsche called this dilemma “eternal return”, he already realized in his time and some think this is new, and in part was right for the horizon he saw in his time, but when the new is not born traditional thinking suffers from aging. and sameness.

It tries to look ‘new’ or ‘creative’, but there is nothing that really changes reality. Great sociocultural problems of our time, moral and even religious, will not change without a new perspective, although redundant one would say a brand new “new”, and in order not to be pure imagination, one must find elements already living that point to the future.

Three new elements are visible: a globalized planet, it is already possible to see itself as a world although different cultural aspects are not yet respected, an exhaustion of the forces of nature, the domination of nature by man was the great mode of modernity, and the end of hunger and misery on the planet, though with resources available for it, has not been realized.

Of course there are many other factors, but they stem from a lack of dialogue with the future, the centralization of autocratic groups, the absence of a networked politics and culture, although the mechanisms for this exist, are countered as “alienation” and even as responsible for problems that exist long before any thought about new technologies.

Apparent death of thought

If there is a sphere beyond pure anthropology and Darwinian  scientism, it is not only in religious thought, but also in thought that goes beyond human, this thought, although in crisis, is present in contemporary philosophy.

scientism, it is not only in religious thought, but also in thought that goes beyond human, this thought, although in crisis, is present in contemporary philosophy.

Peter Sloterdijk wrote The apparent death of thinking: about philosophy and science as a life of exercises, his general theme about contemporary society as “a life of exercises”. The book is the result of several lectures given in 2009 called “unseld” lectures, at the Scientiarum Forum of the University of the Tübingen whose theme was “Anthropology in the discussions of science”, and the author proposes two forms of anthropotechnics, the short-range (You have to change your route) and a long-range one called Selbstverbesserung (yes enhancement).

There is a reinterpretation of Kant and Cassirer due to an ontological excess, which compensates for the “biological deficit”, I explain better, the being who seeks to transcend a deficient biological reality, in such a way that his general “exercise of life” new problems, philosophical and scientific theories. Seeing that the exposition and practices in the usual history of ideas made possible the existence of an improbable science and philosophy, he elaborates a genealogy of the “homo theoretician”, the “pure observer”.

I t analyzes the conditions that arise in the West, the theoretical attitude in general, and science in particular, where he sees what he will call “the murder of an apparent dead” (p. 14), will expand the Husserlian notion of epoché, put in brackets all exteriority and judgment, and expands this concept.

The proposed genealogical method capable of re-elaborating the origin of the product of the sciences, implies what Nietzsche adopted as an attitude of suspicion: “Does the theoretical homo really come from a cradle as high as it is guaranteed from the first days? Or is it better a bastard who wants to impress with fake titles? “(p.57), the provocation has an earlier path already taken.

Ira e Tempo (2006) (Wrath and Time), refers to the product of failure in the space of the polis), psychological (for a psychic disposition to distance oneself from the environment), sociological (through a pedagogy of training the individual) and half-theoretical (the result of a written culture that predisposes the distance of a text, which in turn keeps the distance of the time of life.

This whole framework and to say that we are facing extremely difficult dilemmas for man, for thought and for the civilizing process itself, is beyond and below the pandemic, the outbreak of the real in Marx and the neo-Hegelians, Nietzschean perspectivism, consciousness class in Lukács, Heidegger’s trajectory, the ethical revolution in the natural sciences after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the existentialist commitment, knowledge in Scheler, Kuhn and Foucault, the demystification of isolation in scientific research by Latour and CTS (Science, technology and Society) (pp. 121-129).

Sloterdijk, Peter (2013). Muerte aparente en el pensar. Sobre la filosofía y la ciencia como ejercicio. Siruela. Barcelona.

Cartesian meditations and phenomenology

A small book by Edmund Husserl, which was a compilation of a conference in Paris, was the booklet Meditations Cartesian, where he makes five contributions and it is from there that gives rise to a consistent formulation of phenomenology.

was the booklet Meditations Cartesian, where he makes five contributions and it is from there that gives rise to a consistent formulation of phenomenology.

The path of a Transcendental Ego, unlike idealistic transcendence towards the object, is towards the Other, or other selfs, an overcoming of the status of the transcendent linked to the object, thus describes Husserl: “…. it immediately becomes apparent that the scope of such a theory is much greater than it seems at first, since it also jointly founds a transcendental theory of the objective world […] ”(HUSSERL, 2010, p. 134).

By admitting and relating to the subjectivity of others (another alter ego) both cultural objects and the shared world, it creates an intersubjectivity (HUSSERL, 2010, p. 134-35), now from the transcendental phenomenon “world” a layer of meaning that can be referred to the intersubjective constitution.

The criticism of the experience made by Husserl at the beginning of the Meditations, takes the primacy of the Immanent experience (apoditic of the cogito, attached to logic) while the transcendent experience (the outside world and the others included) does not reduce the transcendental experience towards the object .

Husserl also uses the concept of solipsism which is the idea that there is only the act of thinking and the self, see that in this reasoning the very existence of the object is to put in doubt what is solved by experience, in this case there is a gnosiological solipsism where other beings (human beings and objects) exist only in the mind and not in consciousness.

The phenomenological doctrine is based on the fact that the objective world of science is turned to experience and pre-reflective and pre-scientific thinking because it is linked to subjectivity, to modify this relationship of being in the world, incorporating the world of life (Lebenswelt) from where the need arises for a philosophical anthropology and an epistemology that answers these to this challenge.

As a consequence of this thought, phenomenological ontology emerged as a clear possibility in Husserl’s own project, although he did not initially approve Heidegger’s work.

Another possibility for a philosophical hermeneutics as developed by Hans-Georg Gadamer was also designed there, and the hermeneutic circle was already in project in Heidegger’s thought.

HUSSERL, E. (2010) Meditações cartesianas e conferências de Paris. Tradução de P. M. S. Alves. Lisboa: Centro de Filosofia da Universidade de Lisboa.

The exhaustion of humanism and co-immunity

When Peter Sloterdijk gave his lecture “rules for the human park” on July 17, 1999 in a colloquium dedicated to Heidegger and Lévinas, in the castle of Elmau in Bavaria, despite having theologians in the audience the greatest reaction was from the media, to affirming the emergence of an “anthropotechnical” and genetic manipulation, echoes were heard in France and also in Brazil where a report was published in the “Mais” section of the Daily Folha de São Paulo.

1999 in a colloquium dedicated to Heidegger and Lévinas, in the castle of Elmau in Bavaria, despite having theologians in the audience the greatest reaction was from the media, to affirming the emergence of an “anthropotechnical” and genetic manipulation, echoes were heard in France and also in Brazil where a report was published in the “Mais” section of the Daily Folha de São Paulo.

What the philosopher warned, in his language rich in metaphors to make his intricate philosophy clearer, stated that the work of human domestication had failed, in short this was his response to Heidegger’s Letter on Humanism, and his lecture would become book.

Then came other controversies, about ecology for example, he stated that “we will oscillate between a state of manic waste and depressive parsimony”, in a lecture entitled “about the fury of titans in the 21st century”, that is, between two opposing forces> minimalism and maximalism.

also spoke in that lecture on the decline of the concept of ethics: “… once came from a sense of obligation, virtue. Responsibility only becomes an important category when people do things whose consequences they cannot control ”and warns that the term responsibility is new in philosophy, also in the humanities.

In response to an interview with the newspaper El País, the philosopher who created the concept of co-immunity, said that the current situation will require “the need for a deeper practice of mutualism, that is, generalized mutual protection, as I say in Você Tem que Mudar Sua Vida ”, book without translation into Portuguese.

In addition to the need for what the current situation as a whole, which reveals a global imbalance from nature to the social, indicates that external factor.

Saint John Damascene and pericoresis

Even for those who do not believe in the concept of pericoresis, it is important because it makes the idea of relationship something more substantial, although it is already admitted that man is a relational being, the relationship is full of dualisms and non-Trinitarian interpretations (in the case of Christians) and can lead to indifference.

concept of pericoresis, it is important because it makes the idea of relationship something more substantial, although it is already admitted that man is a relational being, the relationship is full of dualisms and non-Trinitarian interpretations (in the case of Christians) and can lead to indifference.

After resolving the Trinitarian dogma by the Cappadocian priests, who explained that God is One and Triune, are people (hypostasis) and maintain unity (ousia), Damasceno will dwell on the relationship between the three people and create a term also used in philosophy: pericoresis, interpenetration in relationships, that is, the possibility of listening to the Other not just out of respect, which would already be a step, but trying to penetrate and understand the reasons for his thinking.

It was João Damasceno (675-749) who studied this relationship of pericoresis, the term emerges proposing the articulation between the unity and the communion of the Trinity, it seems simple to say this, but difficult to understand and practice, since most relationships exclude the Other which is different, be it of color, race, creed or culture, far ahead of his time João Damasceno was a friend of the Saracens.

In his historical theological journey, he sought to find something to explain the relationship, which was in accordance with what the scriptures said of God and his relevance in history: the articulation between the concept of God that is triune and one, but each one being a natural person (prosopon) and God, João structured the intra-Trinitarian way, based on the Greek concept of person: hypostasis.

In the Greek word it means hypo, which is sub, underneath, and stasis, which is sub-posited; as if it were a support, but in the divine relationship this concept should be expanded and explained.

The term pericoresis emerges in this Patristic Theology, as the articulation between unity and communion of the Trinity, but going further, so the Father is one in the Son and the Son one in the Father, and both are one in the Holy Spirit, so there is an interpretation, it is more what a pure relationship it is to be in the Other.

The problem with some religious interpretations is the static relationship of the three, which is the dualistic relationship that comes from idealistic philosophy, where subject and object are separated and are relational by a type of transcendence, which actually has nothing to do with the Divine mystery nor is it religious.

In a deeper spiritual asceticism is the effort to understand and love the Other who is different, who is not my mirror, does not have my concepts and judgments, does not classify the world as I do, the great tragedy of our days is the lack of pericoresis , and thus of Trinitarian relations.

I think that the pandemic shows us this, even though there is a great pain that kills everyone and that sensitizes many people, that opens the heart to look at the suffering of the other, there are those that close themselves in groups, ideas and schemes to not look at the pain , the hunger and despair that the pandemic has generated, or we wake up together or perish together, staying in our trench is non-relational

Lockdown and frivolity

As the virus expands and begins to arrive more in the interior of Brazil and in many places life remains “normal”, while Europe is gradually trying to return to a new normality, that is, to return to trade and consumerism and the previous hectic life , which Sloterdijk calls frivolity (see in daily El país).

many places life remains “normal”, while Europe is gradually trying to return to a new normality, that is, to return to trade and consumerism and the previous hectic life , which Sloterdijk calls frivolity (see in daily El país).

There are two scenarios, the Brazilian case while some bet that the curve reached the plateau, the new data point to an even greater expansion of the virus, betting that we can contain the serious pandemic situation with little radical measures is proving inefficient.

The reason for the pressure to open trade, more than economic, it is clear that it affects the economy of the whole planet, the real reason in the minds of many people is to return to the day to day of high stress, rush and consumerism to those who have the resources for this.

In Brazil, we have reached the level of 10,000 deaths, both in personal and social life, if we reach a seriousness of a disease or take radical measures or witness the total aggravation of the disease, in the social case, the viral expansion and the worsening of the pandemic.

In the reflection of Sloterdijk, who wrote, in my view, two emblematic books Spheres and Criticism of Cynical Reason, he presents two key concepts that are co-immunity and anthropotechnics.

The first concept of co-community means that we can establish an individual commitment towards mutual protection, which would mark a new worldwide way of facing problems and the concept of anthropotechnics means understanding that the techniques, in this case and is the main concept used by Sloterdijk, the biotechnology, this is genetic manipulation.

When launched, it generated a lot of controversy in Europe, due to the manipulation of genes for example, but now that the main researches in defense of the coronavirus show the importance of the use of antibodies for the production of the vaccine, and the first thing was the genetic sequencing.

The worsening of the Brazilian crisis will require a more serious confinement, or we will see the figures extrapolate and the Health System already practically exhausted.

Confinement is necessary and the return to frivolity must be rethought as a way not only to avoid a major economic crisis, but mainly fairer.

The importance of Droysen’s legacy

We stated last week that both the perspective of Droysen’s Hellenism (he coined the term) and the perspective of the true meaning of his story were broader, long before Gadamer’s criticisms of “romantic” historicism, this author who was a student of Hegel , had already done so and with much property because in addition to being a student, he entered the concept that Hegel is for modern philosophy its founder.

long before Gadamer’s criticisms of “romantic” historicism, this author who was a student of Hegel , had already done so and with much property because in addition to being a student, he entered the concept that Hegel is for modern philosophy its founder.

Johann Gustav Droysen (1808-1884) questioned the principle of historicity, and, long before his time, questioned historians about the “scientific” foundations of a certain perspective and relativism, as well as indirectly questioning Dilthey in an attempt to use history to support the Sciences of the Spirit.

Droysen in his Compendium on History (Grundriss der Historik) that was not suitable for History, since it pretends to be science, to borrow without a method from another perspective of knowledge, which is natural science, even if as an “example”.

The solution presented by him, similar to that of Gadamer, synthesized in the methodological notion of Investigative Understanding (forschendes Verstehen), aimed to give History the possibility of an autonomous science, so for him there is something that precedes the explanation x understanding dualism, which is the history, what we called last week the “form” of thinking.

His 1857/1858 compendium of history (Grundiss der Historik) is available in Spanish (1983) and Italian (1989) versions, still in Portuguese.

Of particular interest, at least for me, was Chapter 3, which deals with the hermeneutical problem of understanding, which gives a sense of the applicability of its method.

The link that we can and should make with the moral question, from the previous topic, can be found on page 386 of her work Teologia dela Storia (Italian translation):

“… we need a Kant, who critically examines not the historical matter, but the theoretical and practical movement before and within history, and who demonstrates, like anything similar to the moral law, an imperative category of history, the living source from which the historical life of humanity flows. ”(DROYSEN, 1966, p. 386)

Droysen observes in what he calls “Systematics” three types of ethical communities: “the natural communities”, “the ideal communities” and “the practical communities” (figure above), and relates to them from history, said thus: “ours systematic resulted from the notion that the historical world is the ethical world, but while conceived from a certain point of view; because the ethical world can be considered under other points of view … ”(Droysen, 1994, p. 413).

Its becoming, therefore, is far from the Hegelian dialectic, but at the same time it dialogues with it.

DROYSEN, J. G. (1966) Teologia dela Storia. Prefazione ala Storia dell´Ellenismo II – 1843. In: Istorica. Lezioni sula Encilopedia e Metodologia dela storia. Trad.: I. Milano – Napoli: Emery.

_______. (1994) Istorica. Lezioni di enciclopédia e metodologia dela storia. Trad. Silvia Caianiello. Napoli: Guida.

Does tradition and innovation have any relationship?

In the cultural sphere, it is often imagined that it does not, or establishes innovation only in the strict scope of culture, while it is related to beliefs, values, and mainly to the forms of social relations that involve the production of wealth, the use of techniques , for example, the transition from oral culture to writing, meant a profound change.

production of wealth, the use of techniques , for example, the transition from oral culture to writing, meant a profound change.

Innovation is linked to some significant cultural change, in general, with the influence of new techniques and production methods for consumption, but the term is broader.

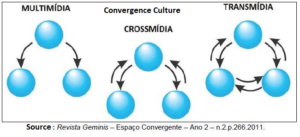

The change today is from the media to the transmedia, that is, the media complement each other, you can make a video from a text or an oral exhibition of a certain culture, so you can talk about the narrative of transmidia, or “ storytelling ”, that is, telling stories.

The term was first used by Professor Marsha Kinder, from the University of Sourthern California (USA), in 1991, but in 2003 Professor Henry Jenkins created a definition that was enshrined in his book “Culture of Convergence”, where he defined it as: “[…] a new aesthetic that emerged in response to the convergence of the media”.

When referring to the term aesthetics, it goes beyond the pure production of consumer products to reach art, culture and, in a way, the belief system as a whole, even though rejection in several areas is common, the process of “innovation ”Advances.

There is also a redefinitionof storytelling, the tradition of oral culture of storytelling, where the tradition is perpetuated changes to a new form, now it becomes the use of audiovisual resources to transmit a story, which can be told in an improvised way (as in oral tradition), but can also be worked on and enriched with visual aids.

JENKINS, Henry. (2006) Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. NY: New York UniversityPress.

Phronesis and serenity

It is no coincidence that Gadamer adopts Phronesis as one of the key elements in his discourse on Truth and Method, incompletely translated as prudence, the term actually to be confused with “wisdom” practice of serenity, free translation.

in his discourse on Truth and Method, incompletely translated as prudence, the term actually to be confused with “wisdom” practice of serenity, free translation.

This is because in our view, Gadamer is a rehabilitator of practical philosophy, those who call for practicality, objectivity (sic! Idealist), are impractical for lack of wisdom, impulsive and active, typical of the society of fatigue.

In the Greek sense, ethics is added, but it is not a private knowledge in the moral sense, but public and social, which aims to minimize exacerbations of ego self-impulsiveness, when placed in a perspective of the work of art reaches a level of universal principle.

This includes the work of art because it was the excessive centralization in the self that reduced the relation of ethics to aesthetics, public amorality, slavery is not a new aesthetic, not even the negativity sometimes necessary to art, is its absence by lack of relationship with ethics and the training process.

Gadamer retrieves phronesis from Aristotle’s proposal in the Nicomachean Ethics, where he seeks to establish the articulation between the universal and the particular, still more between the individual and society, within historical forms of life, but with a common ethos.

One can thus establish a relationship with education, at a time when one talks about a school without a party, one has to think that there is another, without wanting neutrality because it will be an illusion, we explore in a post to follow.

We need to establish the relation of the phonesis with the techné and the episteme, which is the theoretical knowledge and know-how of techné, which is etymologically linked to art (τέχνη) and to crafts.

The harmony between the three forms of wisdom results in practical wisdom, praxis

Dasein and reason

Before entering into the concept of being-in-the-world, a provisional translation of Dasein, it is necessary to understand the extent to which ontology distances itself from Cartesian rationalism, at which point it approaches, for those who desire a deeper dive “Cartesian Meditations” (post) since Husserl was Heidegger’s teacher and he kept some concepts.

The two well-known Cartesian categories for something are res extensia and res cogitans, about which Heidegger wrote: “Doubtless this [with regard to God] needs production and preservation, but within the created entities [or only considering these ] … there is something that needs no other entity, in regard to the production and conservation of creatures, for example of man.

These substances are two: the res cogitans and the res extensa “(Heidegger, 2015, p.144). Thus the Cartesian dualism is not only between two finite substances, which are naturally distinct, but between the two finites and the infinite, and Heidegger clarifies immediately after returning to the medieval ontology, sometimes called fundamental or ontotheology by other authors, the question (Heidegger, 2015, 145), that is, “in the affirmations God is or the world is, we preach the being … the word ‘is’ can not indicate the being each time referred to in the same sense (αυυωυúς, unívoce), since between both there is an infinite difference of bein.

If the meaning of ‘is’ was univocal, then the servant would have the same sense of not created or the uncreated would be demoted to a servant “(idem). It solves the quarrel of the universal, between realists and nominalists, “Being does not perform the function of a simple name [the nominalists thought], since in both cases it is understood to be” (ibid.).

Explicit and surpasses scholasticism ” positive sense of the signification of the s’ as an ‘analogical’ meaning to distinguish it from univocal or merely synonymous signification “(ibid.).

The quotes are of Heidegger’s own to indicate the analogy of being as substance, and extending to contemporaneity neither the analog nor digital are to be, belong only to the ontic, or in our designation to the artifacts.

Finally, it underscores the Cartesian ontology that “falls far short of scholasticism” which left the sense of being and the character of the “universality” of that meaning contained in the idea of substantiality “(ibid.), While acknowledging that even medieval ontology questioned very little this sense.

Although Descartes is able to recover in some respects, he notes for his time and is worth even today, we have not even freed ourselves from the crisis of European thought of the last century, “the Cartesian ontology of the world is still today in force in its fundamental principles”, materiality.

Heidegger, M. Ser e Tempo (Being and time), 10a. Brazilian edition, Trad. Revised by Marcia Sá Cavalcante, Bragança Paulista, SP: Editora Universitária São Francisco, 2015.