Posts Tagged ‘literatura’

What is Love after all

Although Hannah Arendt’s work is not definitive regarding love, the advisor Karl Jaspers himself expressed this, developed and appropriated some fundamental categories in his doctoral thesis “Love in Saint Augustine”.

regarding love, the advisor Karl Jaspers himself expressed this, developed and appropriated some fundamental categories in his doctoral thesis “Love in Saint Augustine”.

According to author George McKenna, in a review of her dissertation, Arendt tried to include a revision in her “The Human Condition”, but it is not very clear in the book (of the Arendt), which is excellent.

If we can also express an expression of this love in ancient Greek literature, such as agape love, the one that differs from eros and philia in this literature, from a Christian point of view the best development made is in fact that of Saint Augustine.

First because he separated this concept from good x evil Manichaeism, a dualism still present in almost all Western philosophy due to idealism and puritanism, then because he was in fact raptured upon discovering divine love, he wrote: “Late I loved you, O beauty so ancient and so young! Too late I loved you! Behold, you lived within me and I was looking for you outside!” (Confessions of Saint Augustine).

Then man must love his neighbor as God’s creation: […] man loves the world as God’s creation; in the world the creature loves the world just as God loves it. This is the realization of a self-denial in which everyone, including yourself, simultaneously reclaims your God-given importance. This achievement is love for others (ARENDT, 1996, p. 93).

Man can love his neighbor as a creation by returning to his origin: “It is only where I can be certain of my own being that I can love my neighbor in his true being, which is in his createdness.” (ARENDT, 1996, p. 95)

In this type of love, man loves the divine essence that exists in himself, in others, in the world, man “loves God in them” (ARENDT, 1996, 95).

The biblical reading also summarizes the law and the Christian prophets as follows (Mt 22, 38-40): “This is the greatest and the first commandment. The second is similar to this: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’. All the Law and the prophets depend on these two commandments.”

Love contains all the virtues: it does not become conceited, it knows how to see where the true signs of happiness, balance and hope are found.

ARENDT, Hannah. (1996) Love and Saint Augustine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Love in western literature

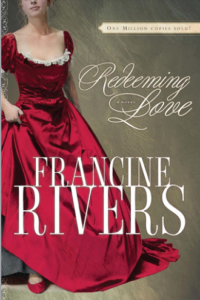

In the previous post we commented on an unusual example in literature which is human love seen from a Christian narrative point of view, there are others of course, but this one is due to the repercussion of Francine Rivers’ work and its recent transformation into a film (2022) and the critics applauded.

In history we can remember some works that marked literature: The Banquet by Plato, The art of loving by Ovid and Sobre el Amor by Plutarco, highlighting in the medieval period The Romance of Tristan and Isolde and Correspondences of Abelard and Heloise.

The philosophical style of the Banquet where there is a predominance of mythological elements that explain or denote love, perhaps hence the idea of platonic love, but which has nothing sublime or non-carnal, what commentators say is that there are homoerotic relationships that are part of the dialogue between partners in relationships.

If there is something elevated, it is in Socrates’ dialogue that defines the so-called philosophical love, which is outside the sentimental sphere and inserted in an idealism (I always remember here that it is for the Greeks to remember Being in its essence, and not something that lives only in mind), is a love that is related to beauty and good.

Ovid (45 BC – 18 AD) is not interested in achieving this asceticism towards a deified love, he seeks to find the necessary tools to realize a more sensual love in a carnal world.

Ovid does not restrict love to the conjugal sphere, Plutarch (45 – 120 AD) sees it within a social and political institution, it is a “path” within marriage towards happiness, like an asceticism of the type that the Greeks considered conceived, this is not a spiritual asceticism.

The romance of Tristan and Isolde and the Correspondences of Abelard and Heloise must be understood in a reality dominated by Christian philosophy in medieval Europe, where the Love of God is indisputable, but love as a union of two bodies is still subject to debate.

This type of romance, inserted in the troubadour tradition, is imbued with a “courtly” element; we find an interesting description of this love in the work of Denis de Rougemont:

What they love is love, it is the very fact of loving. And they act as if they had understood that what opposes love guarantees it and consecrates it in their hearts, to exalt it to infinity in the instant of the absolute obstacle that is death. Tristan likes to feel love, much more than he loves Isolde, the blonde. And Isolde does nothing to keep him close to her: a passionate dream is enough for her.

Among modern novels, I would highlight among the most characteristic: Eugénie Glandet by Honoré de Balzac, Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert and Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, while Eugénie Grandet shows the reality of the material interest surrounding the novel, Madame Bovary will show the lack of lucidity, excess and human selfishness, Anna Karenina shows the tragic colors of her infidelity with her husband Vronsky, but there are two other marriages: a happy marriage (Levin and Kitty) and another that only supports each other (Stiva and Dolly).

ROUGEMONT, Denis de. (1983) Love in the Western World. Transl. Montgomery Belgion. USA: Princeton University Press.

.

Redemption Love

The book was inspired by the biblical narrative of the prophet Hosea, a woman, Angel, who considered herself ruined, with no chance of salvation, a disbeliever of human love, discovers the unshakable love of God, but the context is the gold rush in California in 1850 .

of the prophet Hosea, a woman, Angel, who considered herself ruined, with no chance of salvation, a disbeliever of human love, discovers the unshakable love of God, but the context is the gold rush in California in 1850 .

The time is when men sold their souls for a handful of gold and women sold their bodies for a place to sleep.

Angel sold as a prostitute since she was a child, hates the men who used her and is invaded by contempt and fear of herself, until she meets Michael Hosea, a man who seeks the divine in all things, and believes he has a calling from God to marry Angel.

Redemption Love is a timeless, romantic, epic or tragic classic, it is a story capable of transforming human feelings into an unconditional, redemptive and absolute love that is within the reach of everyone who still thinks about true, lasting and deep love.

But Angel, a victim of her story, as many are today of erotic ideology and contempt for true happiness, runs away and returns to the darkness, away from her husband’s resilient love, from the new that is her definitive cure from a world of shadows and contempt. for the life.

Francine Rivers’ book, far from being just Christian fiction, is an appeal to real human love, the one capable of filling the void of souls that do not accept the passenger, the use of the body as a mere commodity or “instrument” of pleasure, where it is possible to find peace and happiness, of course with all the natural tribulations of life: bills, accidents and getting old, etc.

The book was turned into a film in 2022, written and directed by D. J. Caruso, with the cast: Abigail Cowen, Famke Janssen and Logan Marshall-Green.

Rivers, Francine. Redeeming Love. San Francisco: Multinomah Books, 2007.

The intermittents of death

José Saramago (1922-2010), in addition to his famous book Essay on Blindness, written in 1995 and which later became a film directed by Brazilian Fernando Meirelles and scripted by Don McKellar, wrote many other novels: O memorial do convento (adapted from an opera), The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, Essay on lucidity, and many others, I highlight here As Intermitências da Morte (2005).

Essay on Blindness, written in 1995 and which later became a film directed by Brazilian Fernando Meirelles and scripted by Don McKellar, wrote many other novels: O memorial do convento (adapted from an opera), The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, Essay on lucidity, and many others, I highlight here As Intermitências da Morte (2005).

In 1998, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature, but two works seem prophetic for today: The essay on blindness, which we have already posted, and the Intermitências da Morte.

Skeptical and ironic, Saramago did not fail to notice the dramas of our time, but the unexpected way it ends. Lucidity, I would say using the Heideggerian metaphor that clearing is possible if we penetrate the existential drama of life.

In The Intermittencies of Death, he penetrates into the existential dramas of life, as a religious skeptic, he will also mock the outputs with an answer “from above”, that is, transfer to “another world” our permanently mundane dramas, among them, what it’s life itself.

He says in a passage on page 123: “It is possible that only a painstaking education, one of those that is already becoming rare, along, perhaps, with the more or less superstitious respect that in timid souls the written word usually instills, has led readers, although they were not lacking in reasons to manifest explicit signs of ill contained impatience, not to interrupt what we have been reporting so profusely and to want to be told what it is that, in the meantime, death has been doing since the fatal night when it announced the your return.” (in the photo a picture of Gustav Klimt’s painting).

After inquiring in every book about life, something unusual these days, because all you want is a return to frivolity, the normality of emptiness, the absence of life, consumption and false joys, the author will say in end of the book that death is normality, said like this:

“He stayed in his room all day, had lunch and dinner at the hotel. Watched television until late. Then he got into bed and turned off the light. Didn’t sleep. Death never sleeps.” (Saramago, 2005, p. 189).

And he concludes that his common irony in times when the pandemic was not even dreamed of (his pandemic was The Essay on Blindness), he says about death: “(…) I don’t understand anything, talking to you is the same as having fallen into a labyrinth without doors, Now that’s an excellent definition of life, You’re not life, I’m much less complicated than it, (…)” (Saramago, 2005, p. 198). Oh what a pity, a pity even that Saramago had never believed in a true life, this disbelief is also in all his work, especially “The Gospel According to Jesus Christ” (1991), but at least he was not indifferent to the theme, something “bothered him”.

SARAMAGO, José. (2005) The intermittence of death. Brazil, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Faleceu Alfredo Bosi

Nasci na mesma data de Alfredo Bosi, mas não no mesmo ano, ele nasceu em 26 de agosto de 1936, eu sou mais novo, foi um grande crítico literário e antecipou algumas questões, como a crítica ao eurocentrismo, e revisitou o modernismo, separando-o por exemplo, do Macunaíma de Mário de Andrade, Bosi faleceu de Covid hoje (7/4).

Ao rever Macunaíma, onde há uma “narrativa mitológica” e de fato, Macunaíma é “a multiplicidade do ser, é a fratura insanável do ´eu sou trezentos´, é enfim a instabilidade comum ao poeta e ao heroi que tem por efeito a renuncia aos modos-de-existir passados e recentes”. (BOSI, Céu, inferno, Ática, p. 206).

Descreve com maior fidelidade a intencionalidade de Mário de Andrade, ao ressaltar que Macunaíma perde a proteção de Ci Mãe do Mato e a de Vei do Sol, amulhera-se com uma portuguesa, mas nem por isso adquire identidade fixa, branca e ‘civilizada’. O seu destino, aliás, vem a ser precisamente este: não assumir nenhuma identidade constante” (BOSI, Céu, Inferno, 1988, p. 206).

Também é diferenciada e interessante a sua definição de cultura, que está no livro “Dialética da Colonização” (Bosi, Cia. das Letras, 1992), que é definida como “colo”, onde é “particípio passado é cultus e o participio futuro é culturus” (Bosi, 1992, p. 11), e também colo significou no latim “eu moro, eu ocupo a terra, e por exemplo, eu trabalho, eu cultivo o campo” (idem).

Segue afirmando que o contrário de colo é incola, “o habitante, outro é inquilinus, aquele que reside em terra alheia” (ibidem), por ultimo vai derivar daí a ideia de colonização, onde “colonus é o que cultiva uma propriedade rural em vez do seu dono, o seu feitor no sentido técnico e legal da palavra” (BOSI, 1992, p. 11).

Deixa um legado imenso que ajuda a diferenciar brasilidade de falso patriotismo ou de apologia simbólica ao “colo”.