Posts Tagged ‘ontologia’

Totality, infinity, the Other and unity

Infinity is a theme worked on in contemporary phenomenology by Emanuel Lévinas. In the lower Middle Ages, Plotinus had developed his theme in connection with the one.

Emanuel Lévinas. In the lower Middle Ages, Plotinus had developed his theme in connection with the one.

Plotinus (203-270 AD), the priests of the early Church (patristics), sages and saints for a millennium and a half, until the High Middle Ages, based on 3 hypostases: the one, the soul and intelligence (nous), but our reasoning does not capture that which goes beyond finitude, it is good to remember that zero and infinity began to be worked on in modern mathematics and were fundamental to the development of differential and integral calculus.

We have already dealt with the question of difference and identity in the previous post, simplifying them (just for didactic reasons, as the subject is complex), identity is what makes something unique and distinct and brings it closer to essence, while difference is an individual or object, whether physical or abstract, they are interrelated and are fundamental to understanding the nature of being in the world in different contemporary discourses and here we are interested in the question of the one.

Lévinas’ work takes up the question of Totality and Infinity, he deals with the question of alterity (the other), treating it with the moral question, thinking of it for current times, starting from metaphysics (which was already a question for the Greeks) and now thinking of the totality of meaning of absolute knowledge (which is a current question, for Hegel and Heidegger, for example) and thinks of an ethical knowledge of openness in relation to the world and the Other.

Lévinas uses the phenomenological method with a non-totalizable horizon, opposing it to the idea of infinity, which are different, thus treating them in a dialectic of the Other and the Same, freeing them from logical categories and also from ontologies (in this he differs from Heidegger).

The infinite characterizes his alterity, in this sense the Other and thus cannot be reduced to the identical and the same, so the concept of identity becomes subjective because its totality implies a globalizing thought and for this reason it is still tied to idealism.

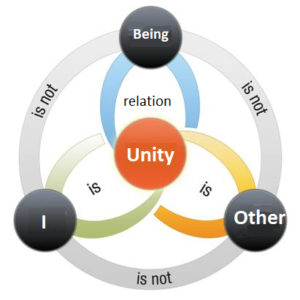

Thus his identity is a synthetic alterity and we can only experience infinity in the relationship with the Other, and so he creates the idea of the “desire for infinity” and this refers to God, there is neither the experience of the One nor that which is realized in the encounter with the Other: unity.

His God is unreachable, he is a vertical God, trapped in this infinitude, the other is a “vestige of the infinite” and not a path to the One, so his concept of desire is thought of as a lack or need that is completed with the other.

Although he doesn’t overcome idealistic subjectivity, Lévinas criticizes the reduction of the Other to the same, what he calls the objectification of Being (or reification, res – thing).

If we have an experience of compassion or communion with the Other, we can achieve unity, which is only possible from the One, who is supra-substantial (Boethius) or as a participant in the “uncreated light” (Scotus) that clarifies us, and points to ontological and theological divergence.

Levinas, E. (1988) Totalidade e Infinito, transl. José Pinto Ferreira, Lisbon: Ed. 70.

Difference, identity and the One

One question for the one is how to live identity and difference. What happens is that dualism starts from difference to try to find unity. If we start from the one, difference is welcomed as “rays coming from the same sun” or as colors that make up white light.

What happens is that dualism starts from difference to try to find unity. If we start from the one, difference is welcomed as “rays coming from the same sun” or as colors that make up white light.

In philosophy, the question of the universal and the particular is embedded in the question of identity, through the question: are two things (quid) sharing the same properties the same thing? or how can a set of unique characteristics of a unity be used to define what an object is or what a person is?

Boethius was aware of the term hypostasis and among it is the proposition of person presented by Plotinus and Boethius transforms it into: Individual Substance of Rational Nature, so person principle is present in Plotinus as Mind (nous*), Soul (its hypostases with the One) and body (common Nature).

The use of the terms here: thing, persons and objects are intentional, because if used as quidity (what is this) one speaks of essence as referring to the real nature of something and at the same time describes the properties that a specific substance shares with others of the same kind (the universals).

Difference is then defined as the variation of properties (or virtues) of the species.

However, hecceity is what makes the essence individuate and be in the world, and so despite (or more correctly, because of) the differences it is one in its essence, the problem that remains is that the essence is a first substance in Aristotelian metaphysics.

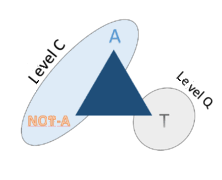

If we look at the diagram of Duns Scotus’ hecceity that has already been exposed, he worked on both the Categories of Aristotle and the universals of Boethius, due to adding a kind of light of the One-Eternal to his expression in Ordinatio I, d. 3, p. 1, q. 46, where human knowledge is capable of the eternal (the one of Plotinus), where there can be a special illumination of the uncreated light.

Scotus puts it this way: “ … with regard to what can be known, I question whether any certain and integral truth can be naturally known by the human intellect in this life without a special illumination of the uncreated light?”, and this is the basis of the question of this light being present in the hecceity of the particulars with the universal.

The metaphor of light is appropriate if we think of quantum phenomena as a substantial nature, and we can also make a synecdoche of Boethius’ supra-substantial to express God in his reading of Porphyry’s tree, both of which have to do with knowledge.

It’s not a comparison or an analogy, because it’s written in the biblical book Genesis the fiat lux (Genesis 1:3) God said: “Let there be light!” And the light was made“ and thus separated the light from the darkness, but darkness here has no demonic meaning but rather the absence of light, or what we put in the previous diagram of the One, ”Chaos matter”, a chaos-matter, which today is called dark matter.

In this way, hecceity can be realized “with a special illumination of the uncreated light” and unity alone, since the One is inseparable, indivisible and is not a category or an object.

*nous Greek has no good translation into English or Portuguese, it could be mind or intellect.

Scotus, John Duns. (1973) Seleção de Textos. In: Coleção Os Pensadores. Brazil, São Paulo: Abril Cultural.

Evil as a thing

Plotinus’ greatest influence on Augustine comes from metaplatonism*, which is a mystical vision.

which is a mystical vision.

Augustine’s overcoming of Manichaeism comes from the question: since all created things are good, each according to its own way, kind and order, where does evil come from? Is there a place for evil in this “divine order” of the world? Augustine answers this question:

“[…] evil is nothing other than the corruption of either the natural mode, species or order. Evil nature is therefore that which is corrupted, because that which is not corrupted is good. But even when corrupted, nature is still good; when corrupted, it is evil. (AGOS TINHO, 2005, ch. 4)”.

The phrase may seem contradictory, but biblical exegesis explains it in the letter to the Romans (Rom 6:20-21): “When you were slaves to sin, you were free in regard to righteousness. What fruit did you bear then? Fruit of which you are now ashamed. Their end is death,” so the fruit of evil (sin) is death and therefore perishes.

In other words, evil, in the Augustinian conception, has no ontological existence, it is not, therefore, a principle of force antagonistically equated with good, as the Manichaeans supposed, so evil is the absence of good.

A more contemporary philosopher Étienne Gilson (1884-1978) states:

“As a consequence of this doctrine, it is not enough to admit that the Manicheans were wrong to consider evil as a being, since it is a pure absence of being; one must go further and say that, being nothing by definition, Evil cannot even be conceived outside of a good. For there to be evil, there must be privation; therefore, there must be a private thing. Now, as such, this thing is good, and only as private is it evil. What it is not has no defects. So every time we speak of evil, we implicitly assume the presence of a good which, not being everything it should be, is therefore evil. Evil is not just a deprivation, it is a deprivation that resides in a good as well as in its subject (GILSON, 2006, p. 273-4).

Hannah Arendt, whose doctoral thesis was Love in St. Augustine (Lisbon: Instituto Piaget, 1997), also states that evil is no longer [just] an individual issue but a social phenomenon, where individuals are manipulated and used as instruments for harmful actions (in the image, René Magritte’s painting Golconda).

According to Christian doctrine, a greater good is derived from an evil, so when we react to evil by paying with evil, in the logic of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, characteristic of today’s wars, we don’t eliminate evil, we just make it continue to exist, whose final destination is that it will perish, but causing greater damage.

This is also the case in our daily lives: if we repay evil with good, we disarm its trap and allow its actions to die through their own ineffectiveness; they can hurt and even kill (as in wars), but they won’t last infinitely, because they are finite by nature.

*we defined in the previous post (see).

Augustine, Saint. (2005) The Nature of Good. Translation by Carlos Ancêde Nougué, introduction by Sidney Silveira. Brazil, Rio de Janeiro: Sétimo Selo.

Gilson, Étienne. (2006) Introduction to the study of St. Augustine. Translated by Cristiane Negreiros Abbud Ayoub. Brazil, São Paulo: Discurso Editorial; Paulus.

Dualism and the One

A brief review of the issues between being and essence, we ended by pointing out the historical and philosophical roots of modern idealism, even though the idea today is different from the Greek eidos, the form or elaboration of its essence or fundamental nature, hence quidity, haecceity and the modern thing (which has become res), the reification of Being.

pointing out the historical and philosophical roots of modern idealism, even though the idea today is different from the Greek eidos, the form or elaboration of its essence or fundamental nature, hence quidity, haecceity and the modern thing (which has become res), the reification of Being.

This is necessary, although insufficient, to return to the question of dualism. Plotinus does not see the one as a concept or a definition, it is an absolute unity, being perfect and indivisible, it is the origin of existence and the order of the universe.

So Plotinus is not a Neoplatonist, in the sense of a follower or a revision of it, from the One emanates all subsistent realities, it is not even the transcendent of modernity, nor the dualism of Parmenides: Being is and non-being is not, it is beyond and there is a certain oriental influence.

In the Enneads, he comments on Aristotle, the Stoics and, above all, Plato, which is why he is seen as neoplatonic, but the meaning of neo here is not the same as that of neokantians like Otto Liebmann and Friedrich Albert Lange, or neologicists like the Vienna Circle, Plotinus’ thought can be called meta-platonic in the sense of “beyond”, like metaphysics, in origin beyond physis (Plotinus traveled to Persia and India and know the oriental philosophy).

For Plotinus there can only be one principle for all things (mentioned above): the One and the Good, as it seems to be in the philosophy of Parmenides and Plato (the High Good), but reality and its realities are fractured, so the principle is above Being.

This could lead to the question that the One does not exist, but Plotinus states that the One cannot be subject to a “Universal spirit”, the spirit is divided into forms and concepts, and it is because of the gap in this One that we fall into the opposition of subject and object in modernity.

So isn’t it a paradox to be beyond being and language (ontological principle) ? the principle described by Plotinus in the Enneads is: the infinite, unlimited and formless, haven’t we fallen back into a void now of a “non-being” ? procession” (in the sense of proceeding) is the way in which beings emanate and is opposed to [a type of] creation that implies reflection, time and division, so all beings emanate from the one (light emanates from the sun, for example) and the shadow is the absence of light, dualism (and Manichaeism) is not a principle but an effect.

The creation that is the principle of everything for Plotinus comes from Chaos, very close to the contemporary definition, such as E. Lorenz’s butterfly effect (George J. Seidel, 1992, p. 211).

Certainly from here Augustine of Hippo draws his principle of Evil as the absence of good, and this undermines his philosophical Manichaeism, but his mystical principle is not the One, but the very Trinitarian essence of God from which all things “emanate”.

Thus the very difference between Plato’s two worlds: the sensible and the intelligible (of ideas) is not a reality in Plotinus, but his mysticism is diffuse, the One emanates but is not emanated, and there is no possibility of an Emanu-el in Plotinus (the term el in Hebrew is God, such as Daniel, Gabriel, etc.).

The One is only possible if it is understood as having a presence emanating from Him among men; without His presence in history, there would only be an absolute High Good that does not emanate from physis.

SEIDEL, G. J. Chaos in Plotinus, Revue de Philosophie Ancienne, V. 10, n. 2, 1992, p. 211-220.

Being, Essence and Haecceity

The long debate between nominalists and realists, which became  more profound in the Lower Middle Ages, involved two great philosophers and theologians Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus, so essence answers the question: what is it? while essence or quidity: what exists?

more profound in the Lower Middle Ages, involved two great philosophers and theologians Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus, so essence answers the question: what is it? while essence or quidity: what exists?

The fundamental thesis of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), The Being and the Essence, is still under the domain of realism, where he believes that both the being and the essence have an existence independent of the human mind, for Duns Scotus essence is the formal determination of the being.

Duns Scotus (1265-1308), until recently seen as a nominalist, is now more correctly referred to as a moderate realist. In the Ordinatio, his main work, he develops theological and philosophical ideas that go beyond metaphysics and epistemology, also addressing the nature of God.

In his Ordinatio I, d. 3, p. 1, q. 46, he poses the problem of human knowledge with the following question: “ … with regard to what can be known, I ask whether any certain and integral truth can be naturally known by the human intellect in this life without a special illumination of uncreated light?” And so a proto-principle of uncertainty is formulated long before modern physics and the quantum reformulation of nature (the uncertainty principle was enunciated by physicist Werner Heisenberg, the source of quantum mechanics).

Not only does he discuss the medieval principles of realism, but he also returns to Augustine, formulating his vision as: “let us contemplate the indestructible truth from which we can define how the human mind should be according to eternal reasons” (Ord. I, d. 3, p. 1, q. 4, n. 202) and goes on to present various arguments about proto-certainty.

His polemic with the medieval realists is long and deserves a thorough study, and only after these readings can we understand his (polemical!) conclusions when he affirms what is again an anticipation of the use of technical apparatuses in modernity, doubting the senses that see only appearance, he says in book XV On the Trinity, chap. 12 or 32:

“Far be it from us to doubt that what we learn through the bodily senses is true, for through them we learn heaven, earth, the sea and all that is contained in them,” [and so] “If we do not doubt the truths of the senses, it is evident that we are not deceived either. Therefore, we are certain of what is known through the senses” (Ord. I, d. 3, p. 1, q. 4, n. 225), various authors have discussed this (Paul Moser and L. Honnefelder).

The importance and recovery of Duns Scotus is clear from Heidegger’s use of his principle of haecceity, although not exactly the same, which explores the question of the singularity and individuality of the human being, in his concept of Dasein.

His sentence about seeing everything as things and objects has limits: “In fact, if for all knowledge the abstracted representation of the thing itself concurs, and if one cannot judge when it represents itself as such and when it represents itself as such, one cannot judge when it represents as being an object – then, whatever the other competing factors, there can be no certainty by which to distinguish the true from the credible. Therefore, these reasons seem to conclude that everything is uncertain, which is the opinion of the scholars” (Ord. I, d. 3, p. 1, q. 4, n. 222) and modernity falls into this reification.

Is there something or someone immutable in the universe, and for those who believe in the eternal: who is he?

Scotus, J. The Ordinatio of Blessed John Duns Scotus: Vol. 1, Transl. Peter L. P. Simpson. USA: Independently pub., 2022.

The Other, ontology and the Trinitarian

The Other has definitely entered more recent Western thought, although the question of the “neighbor” existed in Christian thought, it was understood as a “goodness”.

the question of the “neighbor” existed in Christian thought, it was understood as a “goodness”.

This is because Western thought is marked by an ethical humanism, humanitas (we’ve already mentioned this) in the sense that the civilizing process must contemplate both human nature and goodness, which is why we began the journey of the category Other through Lévinas.

Although influenced by Husserl’s phenomenology and Heidegger’s ontology, Levinas’ (1905-1995) thinking starts from the idea of humanitarian ethics and not ontology.

The influence is clear in his doctoral thesis La Théorie de l’Intuition dans la Phénoménologie de Husserl (1930) and he continues to write articles on both authors, some of which are later collected in his En Découvrant l’Existence avec Husserl et Heidegger (1949).

He observes that Western thought was dominated by Being until the end of the Middle Ages and then replaced by the self, his dialogues include Plato,

Levinas’ thinking starts from the idea that Ethics, and not Ontology, in 1949 he met Martin Buber (author of I-Thou) and received the seed that the place of others is indispensable for our existential realization, but solidifies his idea that ethics is critical and therefore precedes ontology, which is dogmatic, it is good to remember that both had strong Jewish influences.

Thus, Levinas’ category of Infinity refers neither to the cosmological question nor to the idea of Another Being; it is tied to idealism in the aspect of affirming the freedom of the cognizing subject in the face of the exteriority of the cognizable object, thus universalizing reason.

Remember that already in Plato the Good is the functional aspect of the One, it is above the substance or essence, the One that will be treated by the Neoplatonist Plotinus who influences Augustine of Hippo, in the work De trinitate that took almost 20 years to complete, Augustine sees it as Being, and it is undoubtedly a dogmatic aspect, which is the existence beyond the Self and the Other, a Being.

Boethius, a reader of Augustine and translator of Porphyry, for many the first scholastic, affirmed that this Being is neither being nor substance, but ultra-substance, his thought can be concluded as: “Substance is responsible for unity; relationship makes the Trinity”.

We speak of unity tied to humanitas and we need to speak of Trinity, there is the Third Being.

Augustine, St. (2008) De trinitate, books IX and XIII, Transl. Arnaldo do Espírito Santo/Domingos L. Dias/João Beato/Maria Cristina Castro-Maia de Sousa Pimentel. Portugal, Covilhã, LusoSofia:press.

Boecius. (2016) Consolações Filosóficas. Trad. Luís M. G. Cerqueira, Portugal. Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. (pdf)

Buber, Martin. (2006) Eu e tu. Transl. Newton A. Von Zuben. São Paulo, Ed. Centauro. (pdf).

Levinas, E. (1980) Totalidade e Infinito, Trad. José Pinto Ribeiro. Portugal, Lisbon: Ed. 70. (pdf)

Ontological thinking, the third included and the Other

Since ancient times, ontological thinking has admitted two levels of reality (it could be truth, but aletheia since the Greek classics is something else), Parmenides summarized it in being is and non-being is not, Heraclitus went further by discovering that everything flows, we can’t pass by the same river twice because the waters flow over us, but it is the river is, although it changes.

(it could be truth, but aletheia since the Greek classics is something else), Parmenides summarized it in being is and non-being is not, Heraclitus went further by discovering that everything flows, we can’t pass by the same river twice because the waters flow over us, but it is the river is, although it changes.

This thought evolved into mechanical physics, action and reaction, inertia and movement, attribute and force, in short everything that seems very “natural” today, but quantum mechanics has already gone beyond this and it was Stéphane Lupasco who theorized the third included, already proven by current quantum physics.

This third element reveals a logical paradox that the physicist Barsarab Nicolescu developed as a third level of reality (picture), and went so far as to call for a reform of Education and Thought, stating: “one thing is certain: a large gap between the mentality of the actors and the internal development needs of a type of society invariably accompanies the fall of a civilization” (Nicolescu, 2002), in other times the models were: aristotelian mechanics (immovable motor) and the god of platonic thought (High Good) which are still influencing society today.

As we’ve already mentioned a few times, the thought of Augustine of Hippo, who overcame Manichaeism, his belief prior to Christianity, overcame this dualistic reality and what idealism put into “action” was nothing but an idea, it lacked movement outside of this logic.

The Copernican revolution pointed to the movement of the stars and heliocentrism.

The Copernican revolution pointed to the movement of stars and heliocentrism, today we have a black hole as the center of our galaxy, and we are increasingly penetrating this mystery and that of subatomic particles and facing the tunneling effect (an intermediate state between quantum particles) and wormholes (paths in the universe beyond the space-time dimensions).

Modern thought included the question of the Other, no longer as a not-I, it is a new hermeneutics beyond the affirmation of subject and object (idealist), Paul Ricoeur wrote “The self as other”, Habermas “The inclusion of the other” as a theory of re-knowledge, Byung-Chul Han wrote “The Exclusion of the Other” as the media perspective of our times, Emmanuel Lévinas’ book “Humanism of the Other Man” represents a radical alterity that challenges Western thought and its philosophy of identity, very topical when we think about nationalism.

Martin Buber (I-Thou) goes further and sees in the Other an ontological relationship, it’s not just a question of ethics, it’s the vision of a being-for-the-other in the world, it goes beyond being with the other being, Levinas’ “il y a”, a fundamental step in relationships is to then discover an included third party and think that trinitarian relationships are possible, rare as in the quantum universe, but they do exist.

Nicolescu, Basarab (2002). Manifesto of Transdisciplinarity. SUNY Press.

Convergences and divergences in Eastern philosophy

In criticizing idealism, especially Kant, Byung-Chul Han himself reveals in his book Absence that “Eastern thought turns entirely to immanence” (Han, 2024, p. 41) and although there is a true asceticism in Eastern philosophy, it is dislocated and at the same time close to an ontological sense of Being-for-the-other and is stuck in the as-is.

in his book Absence that “Eastern thought turns entirely to immanence” (Han, 2024, p. 41) and although there is a true asceticism in Eastern philosophy, it is dislocated and at the same time close to an ontological sense of Being-for-the-other and is stuck in the as-is.

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, a revisionist critique of rationalist metaphysics, creates a dualism between that which we can know because it is present in time and space, and is therefore immanent, and that which is outside time and space, and is therefore transcendent; all current quantum physics would be transcendent, and yet for physicists it is immanent, because everything that is not demonstrated still belongs to theoretical physics, such as string theory, for example, this has other dimensions.

He uses the oriental concept of dao, with ideas of mental and bodily balance, but Han places it in the “as-is” of things and the here-and-now, and so it would escape naming, because it is too-high, something that flows because it meanders (p. 41), but we remember that at the center of the Milky Way is a black hole, and theoretical physics now speculates that we may be inside the black hole, and so idealistic and daoist transcendence escapes it, there is a “third included”.

Like the Greek oracle and the Hebrew prophet, Han argues that “the sage exists neither retrospectively nor prospectively… he lives in the present” (Han, 2024, p. 42), but by stating that it “does not have the sharpness and resolution of the instant” (p. 43), he admits that “the instant is linked to the emphasis and resolution of action”, so absence is neither in space nor in time, physics calls this state “intertwining” and it is exactly the third included.

The problem of escaping transcendence and immanence lies in the “trinitarian” aspect in which something theo-transcendent happens, but starting from anthropotechnics, which admits a vision of techné that originally belonged to practical knowledge, without being idealistic empirical, and which anthropotechnics deals with, but the onto aspect of the beyond of the technical and of action escapes it.

There is a convergence of the trinitarian principle with Han’s critique, in the situational there is an “escape” from the “Heideggerian situation” where “Dasein resolutely appropriates itself. It is the supreme of presence. The wayfarer dwells in each present, but does not remain, because permanence has a reference to objects that is too strong” (Han, 2024, p. 43).

He presents a dream of Zhuang Zhou in which he was a “butterfly”: “Forgetting himself, Zhuang Zhou floats between himself and the other” (p. 44), but then goes on to contrast it with the essence, a “dwelling nowhere” of Zen Buddhism, because another Trinitarian transcendence does not exist for Zen Buddhism, it is a rising to heaven infinitely.

I’m reminded of Duns Scotus, who said that we can’t separate the “being” of a thing from what it is.

There is only true asceticism at a Trinitarian stage, it is a divinized immanence or a non-objective transcendence, Being through absence rises to God, so what fills this void is not unknown, it is itself.

Han, B.C. (2024) Ausência: sobre a cultura e a filosofia do extremo oriente. Trad. Rafael Zambonelli. Brazil, Petrópolis, RJ, Vozes.

Eastern spirituality and violence

In analyzing the effects of absence, Byung-Chul’s book, he continues to disagree with F. Jullien’s functionalist view, quoting paragraphs §§68 and 69, which at first glance may deal with the question of effectiveness, but it is not, he can “use the energies of others effortlessly”, and quotes §69 as a functional interpretation: “Laozi also applies this principle to the realm of strategy: a good military man is not ‘bellicose’, that is, as the commentator interprets (Wang bi, §69), he does not endanger himself and does not attack. In other words, “those who are in a position to defeat the enemy do not engage in combat with him” (Han, 2024, p. 29, quoting F. Jullien).

disagree with F. Jullien’s functionalist view, quoting paragraphs §§68 and 69, which at first glance may deal with the question of effectiveness, but it is not, he can “use the energies of others effortlessly”, and quotes §69 as a functional interpretation: “Laozi also applies this principle to the realm of strategy: a good military man is not ‘bellicose’, that is, as the commentator interprets (Wang bi, §69), he does not endanger himself and does not attack. In other words, “those who are in a position to defeat the enemy do not engage in combat with him” (Han, 2024, p. 29, quoting F. Jullien).

So a good military leader, says Han, just makes sure that the enemy doesn’t find a way to attack, he applies pressure, but “without it being fully realized”, and then quotes what Jullien sees as paradoxical formulations: “to set out on an expedition without there being an expedition”, or “to roll up one’s sleeves without there being arms”, or “to throw oneself into the fight without there being an enemy”, or “to hold on tightly without having nannies” (§ 69)” (Han, p. 30 Jullien analyzing Laozi’s quotes).

The contradiction is above the question of victory or defeat, Han points out that Jullien omits the last sentence of §69 which is “the mourner wins” (ai zhe shen, 挨着生) the other contradiction is between the conception of mourning that Laozi uses the symbol ai li used in funeral rites in the sense “to mourn” (ai li, 哀禮), “to lament” (bei, 悲), “to weep” (qi, 泣). (HAN, 2024, p. 31).

The Buddhist emptiness kong (空) is very close to the Taoist emptiness xu (哀), both are absent until they become a non-self, a nobody, a “nameless one” (idem, p. 31), we’ve already dealt with this in another post.

Finally, he explains that the xu of the heart in the oriental sense has no functional interpretation, it’s a feeling, not a calculation or a reasoning, he uses the figure of the empty mirror, by Zhuang Zhou (radically different from Leibniz’s animated mirror, he explains), it doesn’t precede, but accompanies, quoting Zhou:

“the highest human being uses his heart like a mirror. He does not chase after things or go towards them: he reflects them but does not hold them […] he is not a lord (zhu, 生) of knowledge. He is attentive to the smallest details and yet he is inexhaustible and resides beyond the self. He accepts all the things that heaven offers, but he has them as if he had nothing” (Han, 2024, p. 32).

Zen Buddhism is also fond of the figure of the mirror, Han recalls, which illustrates the non-retention (another form of absence) of the empty heart (wu xin, 無心), which in the West would be a “not possessing”, “not wanting” and spiritually a making an emptiness in the soul in order to “listen to the heart”.

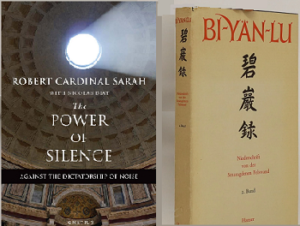

African Cardinal Robert Sarah in his book “The Power of Silence” recalls the noisy Western society and the existential emptiness that it has penetrated, and his famous phrase: “In silence, not only is genuine charity born, but it makes man more like God”, although through different paths it is possible to achieve this.

Byung-Chul Han quoting the Buddhist master Bi Yän Lu using the metaphor of the mirror: “only he who has recognized the nullity of the world and of himself also sees eternal beauty in it” (HAN, 2024, p. 33, quoting Bi Yän Lu).

Han, B.-C. (2024) Ausência: sobre a cultura e a filosofia do extremo oriente. Transl. Rafael Zambonelli, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil: Vozes.

Oriental absence beyond functional calculus

Byung-Chul the void (xu, 虛) as absence does not allow a purely functional interpretation (Han, 2024, p. 16), quoting the book 15 Zhuang Zhou “note: ‘stillness, serenity, absence, emptiness and inaction: this is the balance between heaven and earth’ (tian dan ji mo, xu wu wei, ci tian di zhi ping, 恬淡寂寞, 虛无无为, 此天地之平). The void xu, in the expression xu vu (虚无无), has no functional meaning” (Han, 2024, p. 26).

functional interpretation (Han, 2024, p. 16), quoting the book 15 Zhuang Zhou “note: ‘stillness, serenity, absence, emptiness and inaction: this is the balance between heaven and earth’ (tian dan ji mo, xu wu wei, ci tian di zhi ping, 恬淡寂寞, 虛无无为, 此天地之平). The void xu, in the expression xu vu (虚无无), has no functional meaning” (Han, 2024, p. 26).

He gives several examples noted by Byung-Chul in a footnote, the emptiness of the spokes of a wagon wheel, the emptiness in clay to become a vase, doors and windows of rooms, and criticizes François Julien who interprets according to a functional analysis:

“stripped of all mysticism (since it has no metaphysical orientation), Laozi’s famous return to emptiness is a demand to dissolve the blockages to which the real is subject as soon as it no longer finds any gaps and becomes saturated. When everything is filled, there is no more room for action. When all emptiness is abolished, the margin that allowed the effects to unfold freely is also destroyed” (Han, 2024, p. 27 quoting Julien F.).

He recalls from the story the “frightening appearance of the cripple” who doesn’t have to go to war, and receives “abundant” aid from the state, and also the anecdote of the cook who carves the animal with ease, instead of resolutely cutting, he passes the knife through the cavities already present in the joints.

According to both stories, the interpretation works by suggesting that it increases the effectiveness of the action, also allows for a utilitarian interpretation, but the fact that there are so many cripples and so many useless things in Zhuang’s stories, leads functionality itself into emptiness, these characters appear precisely against utility and efficiency (pg. 28).

I’m also reminded of Western mysticism, where it still exists, that the search for bread, health and social assistance is often also motivated by an existential emptiness, even those who have some social condition are looking for something in a “void” that is not functional, but spiritual.

When someone asks for bread, they are also asking for dignity, citizenship, respect and many others beyond the functional void, the principle of inclusion is not merely rhetorical and should not be functional, it should be ontological as Being-there, but beyond the in Portuguese pre-sente and au-sente (abwesend in German or absent in English), it is just a feel (wow feel in English or Wow Gefühl in German), the word wow in both languages is an expression for wow!), but of course translations are always imperfect.

In Portuguese it would be better to use “sendo” (Portuguese) in the sense of feeling, sein in German and being in English where the verb to be has a stricter meaning than in other languages, here in the sense of existing or subsisting in life, mystically the functional bread is also a mystical bread in Christianity.

Han, B.-C. (2024) Ausência: sobre a cultura e a filosofia do extremo oriente. Transl. Rafael Zambonelli, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil: Vozes.

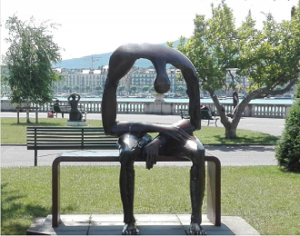

* Albert György’s sculpture entitled “Melancholy” (Lake Geneva) represents “emptiness of a soul” (photo).